To understand the history of your church and the story of religious life in your town or village you need to review two types of surviving evidence: the fabric of the building and documentary sources. The documents available will be considered under the following headings:

The Middle Ages and the Reformation: Foundation of the church; Benefice and clergy; Religious life; the Reformation (below)

From the Reformation to 1660: Religious life; Clergy; Documentary sources for the building (below)

The Middle Ages and Reformation

Foundation of the church

The earliest evidence for your church might be architectural, it might be the mention of a priest in Domesday Book, or it might be an element within the place name (such as Buckminster or Kirby Bellars). Unless your church was a minster, which might pre-date the village, it was probably founded by a wealthy manorial lord as a place for his family and villagers to worship. He would have appointed the priest (a right which passed to his descendants) and provided the land and the first building.

Most medieval churches in England had been founded by the end of the thirteenth century, when new laws made it more difficult to give land to the church. The first documentary reference for many is often in a tax list of 1290, known as the Taxatio. An online database version is available. This may indicate whether the church had any dependent chapelries, or was itself a chapelry of another church elsewhere (a chapelry often had a priest of its own, but originally had no rights of baptism or burial). It will also show you how wealthy your church was, and how that compared with others in the locality.

Benefice and clergy

For a good introduction to the subject in the late medieval period, you might like to read:

Details of the patron, and any changes of patron, will often be given in John Nichols’s History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester. Patronage normally descended by inheritance with the manor, but the right to present a priest (known as the advowson) was a form of property that could be bought and sold independently of the manor. If the church was given to a religious house, you will also find details of that in Nichols’s History. Nichols generally cites his sources, and these can be checked against the original documents in due course.

Henry VIII’s great survey of church wealth, the Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1535 (often referred to simply as the ‘King’s Books’) provides details of the income of each church. This was the first full assessment to be made since the Taxatio of 1290, and the exercise was not repeated until the 18th century. It can be instructive to compare your church with others and see whether variations in wealth between these dates are in line with variations elsewhere. A published edition of the Valor can be found online and the details for Leicester Archdeaconry are on pages 148-86. Although in Latin, the entries are not difficult to understand. Each gives the gross value of the living (‘Valet in …‘) and in the case of parish clergy states whether the living is a ‘vicaria’ or ‘rectoria’ (a rector was entitled to receive all the tithes, whereas a vicar usually only received the small tithes on honey, eggs, etc., and perhaps also on livestock and hay – the precise division could vary from parish to parish). Because income fluctuated, the values were based on an average year (communibus annis). Some entries then have a section headed ‘Inde in’, which gives any agreed deductions. For most parishes the only deductions will be for procurations and synodals, which were fixed sums payable to the diocese, originally to cover the cost of hospitality, visitations and meetings. In theory they were payable by rectors and not vicars, but local practices could differ. The Valor then gives the residual net value (Et rem’), and it is this figure that formed the basis for calculations by church and state for over 250 years. The final figure quoted (‘Xma inde’ or ‘X’ inde’: an abbreviation for decima) is the tenths that were payable from that income to the Crown each year. This figure should be one-tenth of the net sum above.

Many of the bishops’ rolls from the 13th century, which include details of the clergy, have been published by Lincoln Record Society (volumes 2-6, 8-12). The first volume of the rolls of Bishop Wells (LRS volume 3), for example, includes a matriculus and rotulus taxationis of the Archdeaconry of Leicester. Other medieval records concerning the clergy and their parishes that have been published are listed below. The annual Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies mentioned can be found on the shelves beneath the order desk in the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland.

A.K. McHardy, Clerical Poll-Taxes of the Diocese of Lincoln, 1377-1382 (Lincoln Record Society, 81, 1992) – if more than one priest is listed in the parish, there was probably a chantry.

W.G.D. Fletcher, ‘Documents relating to Leicestershire preserved in the Episcopal registers at Lincoln’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, vol. 21 (1891-2), pp. 277-329 [mostly Latin]. This article includes endowments of vicarages, appropriations and the 1510 visitation.

A. Hamilton Thompson, Visitations in the Diocese of Lincoln, 1517-31 (Lincoln Record Society, 33, 1940)

H Salter (ed.) A Subsidy collected in the Diocese of Lincoln in 1526 (Oxford, 1909), pp. 95-124 – includes names and stipends of clergy and chantry priests.

A.P. Moore, ‘Proceedings of the ecclesiastical courts in the Archdeaconry of Leicester, 1516-35’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, vol. 28 (1905-6), pp. 117-220, 593-662 [mostly Latin]

Religious Life

By the later Middle Ages some people were questioning the teachings of the church. An excellent monograph which includes many references to Leicestershire parishes is:

I. Forrest, The Detection of Heresy in Late Medieval England (Oxford, 2005).

Wills can also help to paint a picture of religious life and beliefs in this period, but there are, as yet, no published transcripts of medieval Leicestershire wills, other than those of a few notable persons contained within broader works. They can provide information about pre-Reformation church dedications, images in churches, altar dedications, the existence of parish gilds, personal beliefs and much else besides.

The Reformation

If your church was in the hands of a religious house, the parish would first have felt the effects of the Reformation when that monastery or abbey was dissolved. Volume II of the Victoria County History of Leicestershire provides details of the dissolution.

An Act of 1545 dissolved all chantries and religious gilds which paid first fruits and tenths (a religious tax), and their assets had to be surrendered. Some surrenders were made, but Henry VIII died before the property and other possessions of most of these foundations were transferred. In 1547 his son Edward VI dissolved all remaining chantries and gilds, irrespective of whether or not they were liable to pay first fruits and tenths, and their assets together with endowments for lights and images in parish churches all became vested in the crown. The loss of a chantry priest would have had a major impact on religious life in the parish, as he would have had other pastoral duties and may also have taught local children. Commissioners were appointed under both Acts to draw up lists in each county. The full lists have not survived, but some chantry certificates for Leicestershire are held at The National Archives and have been transcribed and published (in their original languages – sometimes Latin, sometimes English, sometimes a mixture). For more details and transcripts see:

A. Hamilton Thompson, ‘The chantry certificates for Leicestershire’, Reports and papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 30 (1909-10), pp. 463-570.

W.G.D. Fletcher, ‘Some unpublished documents relating to Leicestershire preserved in the Public Record Office’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, vol. 23 (1895-6), pp. 213-52, includes a list of dissolved chantries.

M.E.C. Walcott, ‘Chantries of Leicestershire and the inventory of Olneston’, Reports and papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 10 (1869-70), pp. 331-40

Following the introduction of Edward VI’s new prayer book, vestments were no longer required and medieval chalices were too small for the new Protestant Eucharist. Many people may have suspected feared that these would be next in line for confiscation. Bishops were asked to provide lists of the assets held by churches in within their diocese in 1547, and in 1549 a commission was issued to county sheriffs and justices of the peace ordering inventories to be made for each county. Commissioners were appointed in 1552 to make new lists, which survive for 45 Leicestershire churches, and all but the barest essentials for worship were ordered to be seized in 1553. Verbatim copies of the inventories have been published:

E.H. Day, ‘The Edwardian inventories for Leicestershire’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 31 (1911-12), pp. 441-70

The Reformation was not a single event but a complex series of changes spread over many years. How enthusiastically those changes were embraced varied from parish to parish. For example, the Act of 1547 dissolving chantries, suppressing payments for lights and requiring the removal of any images that were venerated was enforced through the use of diocesan visitations. Other images were not affected by law, but some clergy, parishioners and churchwardens went further and removed or destroyed all images. If churchwardens’ accounts survive, it is worth spending time going through these with a timeline of the key changes beside you, to see how promptly any changes were made.

How did the incumbent himself react to the changes to worship under Edward VI? Or the restoration of Catholicism under Mary? Or the Anglican settlement of Elizabeth? Is there evidence of him resigning or being removed? Or did he simply conform to whatever was required? The records of the presentation and induction of new clergy as well as the Liber Cleri (visitation or call books) are at Lincoln, and are not easy to read, but there are lists of incumbents in John Nichols’s History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, and some churches display them on the wall. Although such lists are not infallible, they are a good starting point and will suffice until the original documents themselves can be checked (which is much easier to do with a rough list to hand).

Wills, especially the religious preamble at the start, can give clues to the changing religious feelings and beliefs of testators or their chosen will writers.

From the Reformation to 1660

The church was now Anglican, but what did that mean? Clergy and people all had their own views about whether the Reformation had gone far enough, or whether it had gone too far. Tensions were high and differed from parish to parish. The civil war also had a strong impact locally, with many royalist clergy dispossessed of their livings. There are several fascinating sources from this period which provide rich detail at parish level, and also allow comparisons to be made between local parishes.

Religious Life

Among the most interesting and useful documents to survive from this period, with the added bonus that they has been transcribed and published, are the records of the visitation of Archbishop Laud shortly after his 1633 appointment as archbishop of Canterbury. Laud was High Church and Arminian, at a time when the church was becoming Calvinist and more reformist. His visitation focused on ‘faults’ found in parishes that were Puritan in outlook, so on a parish be parish basis we learn of things such as the position of the altar or whether clergy wore the surplice. In some places work was ordered to be done, and if churchwardens’ accounts survive it can be instructive to see if his instructions were followed. At St Martin’s church in Leicester, for example (now the Cathedral) the churchwardens were told to take down the loft, which was presumably the remains of the rood loft. The accounts show that this was done, and they paid to hire a horse to travel to the church court being held in Market Harborough to certify this, but then almost immediately afterwards paid for wood to set the loft up again. See:

A.P. Moore, ‘The Metropolitan visitation of Archbishop Laud’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, vol. 29 (1907-8), 479-53.

In 1603, concerns about growing levels of lay dissent and levels of pastoral care prompted an enquiry by the Archbishop of Canterbury which went out through the dioceses to all clergy. The questions asked included details of the number of communicants in each parish, the numbers of male and female dissenters and recusants, details of the patron of each benefice, of impropriations (lay rectors receiving the great tithe, who were obliged to appoint a vicar), benefices served by vicars or curates and their stipend, and the name and educational details of everyone who held more than one living. These are all key questions, which will help you understand religious life in your parish in this period. The replies from Leicestershire parishes have been included in three publications, but each includes different information, emphasising the need, when using published transcripts of any document, to ensure you read any introduction given and understand how and why the transcript was produced.

A.P. Moore, ‘Leicestershire livings in the reign of James I, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, vol. 29 (1907-8), 129-82. Verbatim transcripts of the information provided by clergy. The original documents are held at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland. This article also includes extracts from visitation returns of this period.

C.W. Foster (ed.) State of the Church in the reigns of Elizabeth and James I (Lincoln Record Society, 23, 1926), pp. 286-99. A highly abbreviated version of the diocesan copies of the information that they had collated from the clergy and sent to London. The originals are at Lincolnshire Archives and do not include all the information provided by clergy, as some of this was edited out by the diocesan officials of the time, but do include other information that was added by diocesan officials. This book also includes details of the 1576 visitation.

A. Dyer & D.M. Palliser (eds), The Diocesan Population Returns for 1563 and 1603 (Oxford, 2005), pp. 375-85. As far as the Leicester Archdeaconry material is concerned, this is the most basic of the three publications. Covering the whole country, there was not room to include the whole returns, and as the introduction makes clear ‘the prime purpose of this volume is to make available demographic material’, so everything else is omitted. (The 1563 population returns are also included in here, and are valuable for demographic history, but are less relevant for the history of a church.)

Other visitation records from this period are at Lincolnshire Archives and (for 1619-20) at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland. They can be informative, but the documents are not always easy to read.

Clergy

The Clergy of the Church of England database is not yet complete, but includes details of many clergy between 1540-1835.

Questions to consider in this period include whether the income was adequate to attract an educated man, whether the patron chose educated incumbents with a university degree and whether the incumbent was resident or employed a curate. There are a number of printed sources, other than the 1603 return, which will help:

C.W. Foster, ‘Institutions to benefices in the Diocese of Lincoln, 1540-70’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 24 (1897-8), pp. 1-32, 467-525

W.G.D. Fletcher, ‘Documents relating to Leicestershire preserved in the Episcopal registers at Lincoln’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 22 (1893-4), pp. 109-50 (for visitations of 1510, 1607 and a clergy list of 1605)

A.P. Moore, ‘Subsidies of clergy in the Archdeaconry of Leicester in the seventeenth century’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 27 (1903-4) (for details from a clerical tax of 1614)

Many royalist or traditionalist ministers were ejected from their livings during the civil war. The charges levelled against them were varied and probably contained an element of truth, even if sometimes exaggerated. Details were collected and published by John Walker in the early 18th century, whose papers are held at the Bodleian library. These contain a lot of information about affected parishes, and have been re-edited and published by:

A.G. Matthews, Walker Revised being a Revision of John Walker’s Sufferings of the Clergy during the Grand Rebellion, 1642-60 (Oxford, 1948).

Building

From the end of the middle ages (and often before), renewal and repair was often driven by available funds, and repairs only instigated when absolutely necessary, perhaps at the insistence of archdeacons at their visitation.

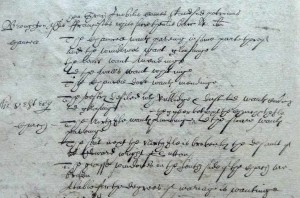

The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland holds several 17th century church survey books (known as lustrationes ecclesiarum), which can tell you a lot about the condition of the fabric at that time. Faults were picked up, such as leaking roofs, uneven floors (perhaps following a burial in the church vaults), inappropriate or broken seating, walls that needed whitewashing (unfortunately rarely saying whether they were just dirty or whether medieval paintings were starting to show through), or a failure to display the royal arms. Some also include other details that would be obtained at a visitation, for example about recusants living in the parish (in this period the word was often used to mean any type of dissenter from the Anglican church, not just Roman Catholics). Some of these surveys are contemporaneous with Archbishop Laud’s visitation (mentioned above), and combining these two sources can create a fuller picture of parish life.

There is a card index to the entries, arranged by parish, which gives the folio number as well as the volume, making it easy to locate the entry you want. A few are in Latin, or a mixture of Latin and English, but most are in English, although the writing is not easy to read unless you have some experience at reading documents of this period. Some of the most interesting points contained within these surveys have been published in a chapter by:

A.P Moore, ‘Leicestershire churches in the times of Charles I’, in A. Dryden, Memorials of Old Leicestershire (London, 1911), pp. 142-172.

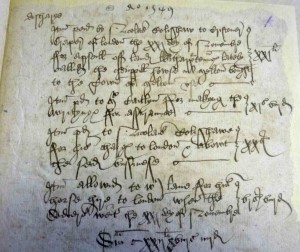

Broughton Astley (from the survey of 1633)

Chauncell The Chauncell wants paveing in some parte thereof and the windowes want glasinge, the leads want mendinge, and the walls want whitinge, The chauncell dore wants mendinge

The vestery The vestry defiled w[i]th Rubbidge & dust and wants Cou[er]ing and glasinge

Church The North Isle wantes plumbing in the gutter betwixt the Church & the Ile and the floare wantes paveinge, The seat next the North Ile is broken by the default of M[aste]r Edward Whight of Sutton, The glasse windowes on the South side of the Church are broken, A table for the degrees of mariage is wantinge

Religious history timeline, 1532-1689

Documents: 1660 to the present day