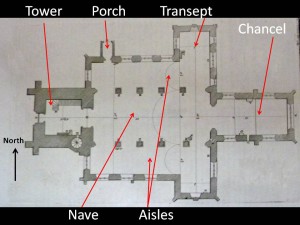

Once you have completed your study of the exterior of the building, you should move inside. Sadly, many churches are kept locked during the day, but there may be a notice board with a contact telephone number, or you may be able to find a contact number online. In most parish churches the main door will be on the south side, opening into the nave. This guide to the interior of the church will therefore start with the nave, aisles and transepts, and then consider the chancel. If you are unsure of the names of the various parts of a church, the plan above should help.

Once you have completed your study of the exterior of the building, you should move inside. Sadly, many churches are kept locked during the day, but there may be a notice board with a contact telephone number, or you may be able to find a contact number online. In most parish churches the main door will be on the south side, opening into the nave. This guide to the interior of the church will therefore start with the nave, aisles and transepts, and then consider the chancel. If you are unsure of the names of the various parts of a church, the plan above should help.

Nave, aisles and transepts

Function

The nave was spacious and was for the people, who not only worshipped there but were responsible for its upkeep. In medieval times most people left a small sum of money, or some corn, to the church when they died. In the gap between the end of those bequests at the Reformation and the introduction of church rates in the 17th century, the fabric of most churches saw some deterioration, which often continued until the Victorian period. It is easy to blame zealous Victorian restorers for the lack of medieval features in so many of our old parish churches, but in some cases the condition of the fabric was so poor that they had little choice other than to rebuild.

Aisles and transepts increased the size of the nave, and also provided additional east ends for side altars. Transepts seem to have gone out of fashion by the late 13th century, perhaps because of a changed liturgy or a rapidly growing population, which made aisles a more practical choice. Some early cruciform-shaped churches with transepts may have experienced the collapse of a central tower over the crossing area between nave and chancel, due to a lack of knowledge of how to provide the support required for the weight, and may have chosen a simpler plan with a western tower when rebuilding. Aisles are common in churches of all periods. In some parts of southern England village and parish are synonymous, but many of Leicestershire’s ancient parishes contained more than one village and by the seventeenth century, and perhaps long before, people from each village within the parish often had their own ‘section’ of the church, whether nave or aisle, worshipping there and taking responsibility for the upkeep of that part of the building. They might even have entered by different doors.

Features and fittings

A full list of the features that can be found in the nave, aisles and transepts of a church would be very long, and this section will concentrate on those which are commonly found and can tell us the most about religious life in the parish. Starting with the font, which is usually near the south door, it takes in the features in the main part of the nave and to the west (towards the tower, or the back of the church) before moving eastwards. That said, every church is different, and some features may be in a different position in your church.

Font

It is surprising how many medieval fonts can be seen in Leicestershire churches, considering that a Parliamentary Ordinance of 1644 required them all to be broken up and replaced by simple basins, as baptism was no longer to be by the total immersion of infants a few days after birth. Some might have been removed from the church and returned when times changed, having survived intact perhaps solely because they made useful troughs for livestock. In many parishes the font is the oldest feature of the building; the church may have been upgraded regularly, but the font was left alone. It was an important indicator of full parish status. Not every medieval church had the right to baptise, and many buildings which look like parish churches were actually chapels of ease, whose worshippers would have to attend their mother church for baptisms and burials. An early font may therefore have been a source of pride, which may help to explain their survival. Originally sited close to the south door, some fonts have been moved several times, raised on plinths of varying height, and may have had several covers over the years. On some medieval fonts it is still possible to see where the first cover was hinged and locked, an essential safeguard not only to prevent the water being taken but also to keep it clean, as the water would not have been changed regularly. Fonts and font covers can be plain or elaborate, depending on how much the parish wanted to spend.

Seating and galleries

Early churches had few or no seats and the weak and arthritic who could not manage to sit on the floor had to ‘go to the wall’, where they could lean, or to integral seats built round the base of pillars. By the later medieval period wooden benches appeared, but it is difficult to know how common they were; very few medieval seats survive in Leicestershire. Longer sermons began to be introduced from the 17th century, and wealthy parishioners responded by instructing village carpenters to make seats for them. By the Georgian period these had mostly been replaced by sturdy uniform box pews (as seen at King’s Norton and Appleby Magna, below) for those who paid a pew rent, and benches at the back or along the wall for children and the poor. Seating throughout the church would have restricted the use of the building and would also have reinforced the social pecking order, ensuring everyone was regularly reminded of their place. Leicestershire still has many churches with box pews, although large numbers were taken out and replaced by pine or deal bench pews in the 19th century. Since the 1980s, many of these Victorian additions have themselves been removed and replaced by chairs, to provide more flexible seating, allowing the church to be used for a wide range of community activities.

West galleries, for a choir and singers, became common in the Georgian period, and galleries were also added to provide additional seating in town churches (such as Market Harborough, where they still survive) or for children (at Appleby Magna, close to a large school). They became unfashionable in the 1850s and most have been removed, although evidence of their fixings can remain.

Royal arms, decalogue, creed, Lord’s prayer, charity boards

There was no requirement to display the royal arms in a church until 1660, but earlier examples do exist, and many more were probably destroyed during the civil war. Originally placed above the chancel arch, they are now more commonly seen on the west wall of the nave, over the south door or on the north wall. It was common for the arms to be updated by over-painting the initials or changing the number at the accession of a new monarch (perhaps when an archdeacon noticed that the wrong monarch was named), so C II R became G R or G R became G II R, G III R or G IV R, often ignoring any required changes to the arms themselves. The royal arms below, at Thornton, purport to be those of George IV, but are earlier. They could have originally been painted during the reigns of George I, II or III; although George IV succeeded to the throne in 1820, these predate the Act of Union of 1800 and still show the arms of France in the second quarter (the claim to the French throne was finally abandoned in 1800). From 1801 the arms of England and Scotland were in separate quarters and the Hanoverian arms were moved to the centre, surmounted by the elector’s bonnet until 1816, and then the royal crown of Hanover, which would be in the centre of these arms if they had been updated correctly.

In the 18th century, Archdeacons began to insist that other painted boards were also hung up in the church, and repainted when necessary, showing the words of the ten commandments (Decalogue), the Apostle’s creed and the Lord’s prayer. Boards with details of parish charities, including endowed schools, were also required to be painted and hung up in the church where all could see them, as a reminder to ensure that money left to charity was distributed according to the wishes of the donor, minimising the risk of loss through fraud or maladministration.

Tables and chests

Always look for old tables in churches, as some may have been used as communion tables in the late 16th or 17th centuries (see below, Chancel). A few tables from this period are still being used for that purpose, while others stand near the entrance, stacked with hymn books and service sheets.

Many churches have an old wooden parish chest, used to store important documents, and often dating from well before Thomas Cromwell’s instruction of 1538 that records of baptisms, marriages and burials were to be kept. Early chests have three locks, one for the incumbent and one for each of the churchwardens.

Pulpit and lectern

After the Reformation the focus of the service moved from the Mass to hearing the word of God. Although medieval pulpits survive in some churches, it was not until 1547 that every church was required to have one. Similar injunctions were issued by Queen Elizabeth and again (presumably because many churches had not complied) by James I. The latter appears to have been effective, as oak pulpits survive in large numbers from this period. Medieval churches, with their thick stone pillars and echoing sound, were not designed for preaching, and many Jacobean pulpits were topped with testers (sounding boards) to improve the auditory experience. Double and triple-decker pulpits also began to be introduced from the later 17th century, with integral lower desks for the priest to conduct the service and for the parish clerk (a lay person) to lead the responses. A good example, from the 18th century, can be seen in King’s Norton (above).

Lecterns (reading desks) would have been used by priests and choirs in medieval times. Their number would have expanded from 1538, when an injunction of Henry VIII required every church to have a copy of the Bible in English. A common form of lectern in the Middle Ages was the eagle, which carried the triple symbolism of being the bird which flew closest to heaven, was the carrier of the Gospels to the corners of the earth and was the symbol of Gospel-writer St John. Many of today’s eagle lecterns date from the late 19th century, and were popular memorial gifts.

Wall paintings and stained glass

From the people’s perspective, medieval services were more informal than those of later periods. Services were long, especially the Sunday High Mass, but people could arrive and leave whenever they wished. They played no part in the service itself, which would have been in Latin and mostly conducted from the chancel, where the screen would absorb most of what was said. For much of the mass the priest had his back to the people and spoke in a low voice (as he was speaking only to God). People were free to meditate, to say their own prayers and to wander round the nave looking at the images in stained glass, wall paintings and carvings to inspire their prayer. Many Leicestershire churches had their plaster scraped from the walls during a 19th century restoration, so few wall paintings survive. Glass was fragile, and many images of saints in the windows would have been permanently destroyed in the 16th and 17th centuries. The easiest way to recognise glass of the 14th and 15th centuries (and to identify which parts have been restored) is from the outside of the church, where the silver nitrate painted on to the surface can most easily be seen.

East end of aisles and transepts

Weekday masses would usually be said at altars which stood at the east end of aisles or transepts, and the survival of a piscina (and occasionally sedilia) in these areas indicates where a medieval altar once stood (an explanation of these terms is given below in the section on the chancel). These side altars were also used for masses for the dead. In the Middle Ages, the very wealthy, or groups of parishioners who had formed themselves into a gild, might have given land to provide a rental income that would pay for the salary of a chantry priest in perpetuity, to say masses for their souls and those of their family or other gild members. Many other parishioners left ten shillings (50p) in their will for a trental, which was a series of 30 masses sung for their soul. These would usually have been performed at an altar at the east end of an aisle or transept. In the case of a permanent chantry, there would sometimes be a screen to create a separate chapel (look for marks in the stonework showing where one might have been). Following the Reformation these altars would no longer have been used, but the areas where they stood were sometimes converted to private chapels for local gentry families, and can contain splendid monuments (as were the chancels of some churches, for example Bottesford, which you can now tour online.

Chancel screen, former rood and clerestory

In the medieval period the nave would have been separated from the chancel by a screen, usually of wood. (Eastwell church has a stone screen, but there is an ironstone quarry in the village, so perhaps stone was easier to find.) A number of these wooden screens have survived, but in Leicestershire it does not seem to have been the fashion to paint them with figures of saints, as seen in so many churches in Norfolk and Devon. Above the screen would have stood images of Christ crucified, flanked by Mary and John (a group known as the rood). A clerestory, the upper part of the nave wall containing a row of windows on each side, was often added to churches in the 15th century and would have provided natural lighting at this level to allow the rood to be seen clearly. In many churches there would have been a walkway (loft) at the level of the rood, so candles could be placed next to the images. In some churches readings would have been made from this platform, there might be an altar (and piscina high up in the wall) and singers and musicians might also have stood there on some occasions, as this short video clip explains. The loft would also have provided the access required to cover the figures at certain points of the liturgical year. Roods and their lofts had to be taken down at the Reformation, but blocking up the access staircase would have been expensive, and perhaps also resisted by any who hoped that the Catholic faith would be permanently restored following the death of Edward VI. Evidence of former rood staircases is common and there are many examples across Leicestershire, either because they were never fully blocked up, or because poor quality infill was removed during a 19th century church restoration.

What to look for in the chancel

In the Middle Ages the chancel was the holiest part of the church, where High Mass was celebrated every Sunday, and the laity (people) were not permitted to enter.

After the Reformation, the chancel was considered to be just another part of the building, no more holier than the rest. It was also used less frequently, as until the mid 19th century, communion services might only take place three or four times a year. The rector was responsible for the upkeep of the chancel, and it might be reduced in size to a fraction of its former length. Some churches built in the 18th or early 19th century do not have a separate chancel, although they will probably have a sanctuary at the east end of the nave,

From the mid 19th century things changed again as two movements which began in the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge swept the country, returning church buildings and the liturgy to something closer to their medieval form.

The main items found within a chancel that can tell us about the history of the building are as follows:

Altar

Medieval altars comprised a stone tablet (mensa) standing on a base of stone or sometimes wood. Early altars contained relics within them (something believed to have been part of a saint, or something touched by a saint).

The mensa would have five consecration crosses carved into it, one in each corner and one in the middle. Their perceived holiness would have made them a target for Reformers in the late 16th and 17th centuries, and many would have been deliberately smashed.

The communion service in the first prayer book of Edward VI (1549) begins with the priest standing before the middle of the ‘Altar’, but within three years the second prayer book (1552) refers only to a ‘Table’. Within a year the king had died, and its services were replaced under his Catholic sister Queen Mary I by the mass.

The ‘table’ was reintroduced by the Elizabethan church. A few churches still have an Elizabethan table, or one from the 17th century. Some of these have now found an alternative use in the body of the church, as a convenient place to put hymn books, service sheets or guide books.

Sedilia and steps

Sedilia are medieval seats to the south of the position of the medieval altar, where clergy would sit. There are often three, for the priest who sang the mass, the deacon who sang or read the Gospel and the sub-deacon who sang or read the other Bible reading known as the epistle.

As the chancel was the responsibility of the rector, the cost of the sedilia was probably met from the tithes paid by parishioners (one-tenth of the produce of the land). The degree of elaboration can therefore provide an indication of the size of the medieval parish and the prosperity of local farming.

Sometimes all the seats will be at the same level, sometimes they will be stepped, with the highest being nearest the altar. If the seats would not be a comfortable height to sit in today, the floor level has probably changed.

The medieval church may have had steps up to the altar. These were not favoured in the 1640s, but because of the work involved in levelling the chancel, this may not have been done.

From the mid 19th century, three steps came into favour again, to represent the Trinity of God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Piscina

A piscina was a place to wash the mass vessels, and indicates where a medieval altar would have stood. Most take the form of a small niche at arm height in the south wall of the chancel, containing a saucer-shaped base with a drain, and may be incorporated with the sedilia into a single architectural piece.

A drain took the water away to consecrated ground, as it might contain traces of bread and wine, which Catholics believe becomes the actual body and blood of Christ at the mass. After the Reformation, these beliefs were considered superstitious and piscinas fell out of use.

As the altar would always be at the east end, a surviving piscina indicates the length of the medieval chancel, which may differ from the length of the chancel today.

Double piscinas, with two basins in a single niche, are unlikely to be earlier than the 13th century, when priests were instructed to wash their hands before mass using a separate piscina, or later than the 14th century, when they seem to have fallen out of fashion. There is a fine example at Stoke Golding. A pillar piscina has a drain within the pillar. Few survive, but because they can be moved, they may be found tucked away in odd corners of the church.

East wall

This may contain niches for statues and images, which may have been removed at the Reformation.

The window in the east wall of the chancel may be one of the largest in the church, illuminating the altar in the early morning. This was where High Mass would have been celebrated in the Middle Ages.

Easter Sepulchre/ Patron’s tomb

Each year on Good Friday in the late medieval period some consecrated bread and wine (believed to be the physical body and blood of Christ) and a crucifix would be ceremoniously ‘buried’ in an Easter sepulchre against the north wall of the chancel, where they would be watched day and night until they were ‘resurrected’ on Easter Sunday morning. The sepulchre might be a permanent stone structure or a wooden structure brought into the chancel each year; a tomb could also be used.

The wealthy preferred to be buried in a vault under the church rather than in the churchyard, as far to the east as possible, as that was considered the holiest part of the building. A single wealthy patron who had paid for the bulk of the cost of building or rebuilding the church might be afforded the honour of a tomb in the east end of the chancel, on the north side (where there was more room), which would double up annually as the parish’s Easter sepulchre (as at Cossington, pictured above).

Low side windows’

These are narrow, close to the ground, usually at the west end of the chancel and generally late-medieval in style (often with a square top).

Historians cannot agree on their function, and numerous explanations have been put forward. An article by Paul Barnwell published in the journal Ecclesiology Today no 36 published in 2006 (on pp. 49-76) lists 22 theories that have been proposed since the 19th century, including the one that has most caught the public’s imagination over the years, that these were to enable lepers who were not allowed into the church to hear the mass. They might also simply be for ventilation, helping to disperse the incense and smell of tallow candles that had been burning for long periods.

Communion rails

The medieval church had no need for communion rails, as the people were not permitted to enter the chancel. Following the Reformation, Puritans liked to receive communion at their seats in the nave or sitting round the communion table, but that was a step too far for others and became a cause of conflict between the clergy and the people in some parishes.

In an attempt to introduce some order and to preserve the ‘beauty of holiness’ (which was itself a controversial concept in the 17th century), when William Laud became Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633 he insisted that communion tables were placed ‘altar-wise’ (i.e. with the long sides to the east and the west in the manner of a medieval altar) and ‘fenced in’ by rails. Many of these rails were broken down in the 1640s and 1650s, to comply with the Ordinances of Parliament, or because local people had Puritan views.

Most of the communion rails in Anglican churches today are from the 19th or 20th century.

Choir stalls and organs

Most choir stalls were introduced into churches in the Victorian period. Organs may date from the 18th century, but are unlikely to have been in the chancel at that date, as this part of the building would not have been in regular use then. Most early organs would either have been in a west gallery, or somewhere in the nave.

Monuments

People commemorated in the chancel are likely to have been clergy or the wealthiest and most influential of the parishioners, and their monuments can tell you a great deal about the social history of the parish.

From the Elizabethan period much of the money that in earlier centuries might have been spent on the church fabric was instead invested in monuments commemorating members of wealthy families.

Return to Exterior, or Architectural periods

On to Documentary evidence