One of the best ways to begin a study of the building is by walking right round the outside. By thinking about its shape, trying to identify different periods of construction and looking for scars to the fabric where changes have been made, you will start to notice clues to its history.

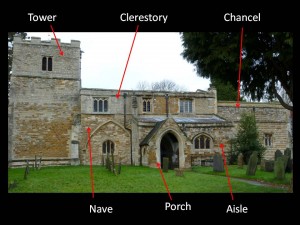

Start by standing to the south (with the chancel to your right). For most churches this side would have contained the usual entrance in the medieval period. Take in the whole length of the building. Does it look as if it was all built in one period, or is it a hotch-potch of different styles? The picture below shows the south front of Lubenham church.

You do not need to be an expert in architecture to realise that this church has had a complex building history, with several periods of alterations, additions and other changes, most clearly apparent by the use of different types of stone, the different shapes of the windows, the scar to the left of the porch (where part of the south aisle has been removed) and a possible increase in the height of both nave and chancel.

Look at the windows in your own church. If their shapes or that of the tracery within them (the stone bands between the glass) are different, they were probably inserted at different times. You may find details of their date in the Leicestershire volume of Pevsner’s Buildings of England series. This guide shows examples of the types of tracery and other architectural features found in Leicestershire churches, and should also help you to assign dates. Consider whether the windows of your church are elaborate versions of each style or a more simple ‘budget’ version. All these observations are telling you about periods of wealth within the local community, not just at the time of construction, but also later. Windows are relatively easy to change, and a wealthy 15th century community was likely to have replaced a 13th century style. If your church appears to be all or mostly of one date, that suggests that there was at least one very wealthy donor at that time, as lots of small donations would not have covered the cost before styles changed. It also implies that there was less money available in later periods for extending, rebuilding or updating. Old architecture was not retained or ‘patched up’ because it was seen as a fine example of its period, but because it was serviceable and replacement was unaffordable.

Is there a clerestory between the nave and the roof? This was a common addition to churches across the country in the 15th century, but Leicestershire has many churches with no clerestory, suggesting that by the 15th century these communities were much poorer than they had been perhaps 100 years earlier, and had too little money to invest in a lighter, brighter church.

What else can you see? Were different types of stone used? Four main types of stone are seen in Leicestershire’s medieval churches. Limestone is a fine cream or grey stone which comes from the limestone belt to the east of the county around Stamford or from north-east Leicestershire, around Saltby. It is cut and laid in blocks and found mainly in areas of the county that were close to the quarry waterways, and on parts of the church where a strong and hard-wearing stone was required, or a fine stone for intricate carved. Ironstone, which is quarried in the Melton and Belvoir areas, is also cut and laid in blocks but is orange and will show signs of weathering, as it is a much softer stone. Away from these stone areas, most medieval churches were built with field stones, which are various shades of brown and irregular in shape, but laid in courses. By the 18th century, new quarrying technology made the hard rocks such as the grey, pink or green-grey diorite in the Charnwood and Croft areas available for building, but until the late 19th century they were still difficult to cut. They were therefore laid as they broke, in large irregular pieces of rock.

Different stones in one church may indicate different periods of construction. Can you see lines where the fabric has been extended? Has the roof line changed? Are there any blocked up doorways, windows or aisles, or any evidence that part of the building has been removed? Does the chancel appear to be more or less lavish than the remainder of the church? The chancel was the responsibility of the rector (which in the medieval period could be a clergyman or a religious house, and after the dissolution of the monasteries could be either a clergyman or a lay person, known as an impropriator). The rector received the tithes (one-tenth of the annual produce of the land and increase in livestock), which were intended to cover this cost as well as providing income for other purposes, but some rectors had little interest in maintaining the building. The upkeep of the rest of the church was the responsibility of the parishioners, and the churchwardens would be admonished by archdeacons and bishops if the parishioners’ part of the building was in poor repair. The extent to which the people could afford to add embellishments to the capitals of an arcade, a clerestory or the other many non-essential features we see in parish churches would depend on levels of individual and communal wealth, and perhaps also on someone to encourage generous donations or to arrange fundraising events, as the fundamental aspects of financing community projects are timeless.

Is there a porch? Porches had a range of religious and secular functions. The first part of the marriage ceremony was conducted there (hence Chaucer’s Wife of Bath tells us that she had had five ‘Housbondes at chirche dore’), as was the service known as the ‘churching of women’, as women could not enter the church after childbirth until they had been ‘churched’. The porch played a part in services during Holy Week, before Easter. It would also have been used for trade, for shelter or just to rest (most had stone seats), and would have protected from rain any official notices pinned to the church door. You can often find a mass dial carved on a stone on or near the south porch, to tell the time, and a fine example can be seen at Thornton.

Think about the size of the building. How many people would it have contained? Can you seen signs of expansion, such as an aisle in a noticeably different style, or contraction, such as the scar at Lubenham where the western part of the south aisle has been removed and the arcade filled in to create an exterior wall? Does the nave seem far larger than necessary – in other words is today’s population much smaller than in the medieval period? Changes to the chancel are likely to reflect liturgical change, and will be considered when we move inside the building.

Before leaving the south front, examine the windows more closely. Most churches were substantially restored and repaired in the 19th century, and Victorian architects copied a whole range of medieval styles, both when building from new and when restoring older buildings. There are two clues to help you to separate original features from later insertions. The first depends on close observation. A window inserted in the 19th century will often have very sharp tracery, because it will have been produced by tools that did not exist in the medieval period, and the stone will show less weathering than the rest of the building. The second clue is pictorial, and requires a little research. Historians will ever be grateful to John Nichols for his monumental History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, now available online through the University of Leicester Special Collections, not just for its transcriptions of medieval documents and information about the parish at the time he was writing, but also for the numerous engravings he included. His volumes contain pictures of virtually every church in Leicestershire as it was in the late 18th and early 19th century. By happy coincidence this just predates the attention that most Leicestershire churches received from Victorian restorers. So if there is now an arched Gothic-style window, but Nichols shows one with a square head, you will know you are looking at an alteration that has been made since the late 18th century.

Now walk to your right and go round to the east end of the building. On some churches you will see a small bellcote above the chancel for a sanctus bell, which was rung at the elevation of the Host. The east window was the most important window in a medieval church, and may be of the best quality. Early medieval churches were quite dark, as the windows were small, but the east window was designed to let as much early morning light into the chancel as possible, to illuminate the most important part of the religious rites – the mass.

While standing at the east end, look along the length of the building at roof level. If you have a tower you may see a triangular scar against the east wall of the tower, especially if there is no clerestory, marking the earlier roof line for a steeper pitched roof.

The east end is often the best external point from which to see the shape of the building. Medieval churches were effectively a series of rooms – a nave, chancel, aisles, chapels, one or perhaps two porches and a tower. Some churches had transepts stretching north and south from a crossing between the nave and chancel, creating a cruciform shape, sometimes with a central tower (for example, St Remigius, Long Clawson). We shall consider the function of aisles, chapels and transepts when we move inside the building. Churches built, or substantially altered, after the Reformation were simpler in form, to suit an Anglican service with far less ritual. The church at Potters Marston, which was probably built in the late 17th century, is a plain rectangular building with no adornment.

Some churches have aisles that extend as far east as the end of the chancel, giving the appearance of two east ends. This created a chapel at the end of the aisle, where there was probably a medieval chantry with its own priest to say mass daily for the benefit of the soul of the founder, his ancestors and descendants. Such chantries were terminated at the Reformation, and their assets confiscated by the Crown. Consider whether the architecture of any chapel is from the same period and as rich as that of the main church, such as at Burton Overy, or less elaborate, like the north chapel at Appleby Magna (below). A wealthy donor might have paid for the chapel but not the church, or could have paid for both. Later generations of that family might have updated just the chapel, but if the donor’s family became impoverished or died out, the chapel would not have been changed when the rest of the church was updated.

Moving to the north side of the church, the same comments apply as for the south, except there will be no mass dial. Any extensions on this side are likely to be Victorian or later, such as vestries, boiler rooms or chimneys. Scars on the north side of the chancel could point to the removal of a Victorian extension, rather than the removal of something older.

Towers, spires and bellcotes

There are around a dozen or so Leicestershire churches where the only part of the medieval building that remains is the tower. That is curious. Population growth or dilapidations may have made it necessary for some churches to be completely replaced in the 19th century, and given the cost involved in providing a new tower with strong enough foundations to bear the weight of the bells, it made sense to leave the old one there if possible. But why were churches in such a poor state if the tower remained in good condition? A medieval tower was probably built to house one or perhaps two small or medium-sized bells which were rung for a few minutes by striking a stationary bell with a hammer or clapper. By the 19th century these towers contained rings of perhaps 5, 6 or 8 bells with a total weight often exceeding two tons, and the science of change ringing had resulted in them being rung by each being swung 360 degrees in quick succession for periods of up to three hours, and sometimes more. Medieval towers were clearly well built, as they withstood this stress. So why was the remainder of the church in such a state? Although several faculties for rebuilding claim the fabric was dilapidated, was this just a device to obtain agreement to changes being made that were driven by fashion? The example of Countesthorpe suggests that the wording in a faculty should not be taken at face value.

Towers were built to house bells, and bells were rung to summon people to prayer, to provide warnings, to tell people that someone had died, to mark the moment in the mass where the bread and wine were consecrated and to mark community events. They have been provided in churches for centuries – a Norman pillar at Stoke Dry church in Rutland, carved in about 1120, includes a picture of a bell-ringer. More than 20 pre-Reformation bells still hang in Leicestershire’s churches, the earliest dating from the 14th century.

Towers had no real need for windows, other than at the level of the bells to let the sound out, and hence their early small lancets remained. Where a suitable stone (such as limestone) was fairly easily obtained, spires might be added in the wealthier parishes. The fashion in Leicestershire was to include tiers of lucernes (small window-like openings) within the spire. Turning a square tower into a spire required skill, and fine broach spires which achieve this through triangular corner sections can be seen at a number of churches, including Hallaton and Oadby, both 13th century. More usually, the spire starts from a flat base at the top of the tower, hidden by a parapet. Two of the finest, and tallest, spires in the county, both with crockets typical of the Decorated period, can be seen at Bottesford and at Queniborough.

Parishes that could afford neither a spire nor even a tower built a bellcote at the west end of the nave to house one or two small bells.

Site

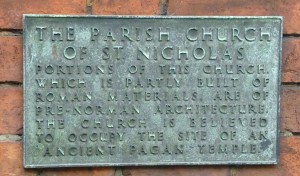

The church may be the oldest building in a town or village, but its site may be more ancient than any visible architecture, so before moving inside, it is worth thinking about why the church might have been built in that spot. We know little about the range of beliefs that existed in this country in the centuries before the arrival of St Augustine in 596, nor of Pope Gregory’s initial instructions, but a subsequent letter from the Pope has survived in which St Augustine was instructed:

‘that the idol temples of that race should by no means be destroyed, but only the idols in them. Take holy water and sprinkle it in these shrines, built altars and place relics in them …’. (quoted in Richard Morris, Churches in the Landscape).

Some of our churches may therefore stand on sites that were considered sacred in the 6th century, and indeed those temples may themselves have been erected on sites that were important to those with even earlier beliefs. Trees, springs and natural wells might have been venerated in ancient times, although care needs to be taken not too read too much into such features, as it can be difficult to date venerable yew trees, and Christian worship needed a convenient source of water. Circular churchyards or neighbouring earthworks might mark a significant site, but are also difficult to date. Breedon on the Hill stands in an iron age hillfort, as do some other churches in Britain and Ireland, but was it simply a vacant site when the first church was built there, and was it chosen for its visibility or for some other reason? We can only surmise. Hills were often chosen for churches, so they could be seen from miles around as a statement of faith, and perhaps so that their towers could double-up as lookouts or beacons.

A few churches were built on sites that are known to have some significance. The church at Wistow is some distance from any houses, on low-lying ground which floods easily and does not seem ideally suited for building a church. However the place-name provides a clue, as it means the holy place of Wigstan, and the church (dedicated to St Wistan) was said to have been built on the spot where St Wigstan (a Mercian royal prince) was murdered, and where miracles occurred. It has been suggested that St Wistan’s church in Wigstan was built where the body rested on its way back to Repton.

Other churches which are a long way from the village centre suggest that the village may have moved, its people perhaps choosing the best quality land after a period of population contraction. Sites in the centre of a village are more usual, as is proximity to the manor house, as manor houses are usually built on the site of earlier manors, and in many cases it would have been the lord of the manor who gave the land for the first church to be built.

Documentary evidence