There was anger within the town when it was announced that a Government Health Inspector, William Lee, would visit. Many townspeople saw no need for improvements to be forced upon them. They feared the cost and the loss of local control (as they had recently experienced with the Poor Law and the building of Loughborough Union Workhouse).

Those opposing government involvement called a meeting, to prepare their arguments for why the nature and timing of improvements should be left to local discretion. The meeting was reported in the Leicestershire newspapers – which were read by William Lee, who was in the county at the time, conducting an inspection at Market Harborough. He was therefore fully prepared for his reception in Loughborough.

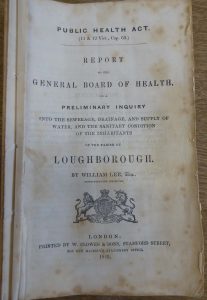

William Lee arrived on 12 June 1849 and stayed for six days. He visited many streets and yards in the town, inspected the lodging houses at night and assessed the adequacy of the burial grounds. He heard evidence from doctors, other professionals, builders and ordinary working people.

James Jackson lived in a cottage in Queen Street. He and his wife lived with seven children aged from 2 to 22. Three other children had died, one from smallpox, one from measles and one from ‘inflammation’. Mr & Mrs Jackson and their seven living children had only two bedrooms in their house. They shared a single privy (a basic non-flushing toilet) with the families living in six other houses.

“In parts, the water was found to be so bad that the tenants could not use it, but had to beg or steal it from other pumps, while some had to travel 200 or 250 yards for the water they used for cooking.”

A lodging house in The Rushes had two lodging rooms occupied by 24 people, 15 male and 9 female. One of the men had recently arrived from Birmingham, where he had caught typhus fever and was still ill. (Typhus is an infection spread by lice or fleas.)

Lee’s conclusions were stark. Preventable sickness and mortality in Loughborough were excessive. The privies were unhealthy. The town’s wells and pumps were polluted.

His main recommendations (at an estimated cost of £21,980) were

- the establishment of an elected local board of health.

- the provision of a constant supply of clean water from the Wood Brook, with a ‘gathering ground’ at Nanpantan.

- a complete ‘system of deeper drainage’

- the cleaning out of all cesspools

- the replacement of privies with ‘soil pan apparatus’ or water closets, which would flush away the contents into the ‘drains’ (sewers).

Loughborough’s existing Board of Guardians, their Sanitary Committee and the Board of Surveyors objected to Lee’s recommendations. They claimed that their insistence that property owners paid for specific improvements for drainage (the Victorian term for basic sewerage) had already reduced deaths, and that Loughborough already had an adequate supply of clean water.