Between 1833 and 1901 education became increasingly controlled by the state. Schools became eligible for state grants, and the conditions attached, backed by government inspection, began to drive up standards of teaching and of school premises. The introduction of a pupil-teacher scheme from 1846 reduced the number of schools using monitors, other than for the infants’ class. Building grants, population growth, and a requirement from 1870 for enough places to be made available for all children, resulted in larger schools. Small private schools started to be squeezed out, unless they could offer specialist teaching.

This guide will lead you through the sources you need to check to compile a history of education in your parish between 1833 and 1901. Sources appear in bold red bullet points, while the text provides examples and explanations to help you to interpret your findings.

Another useful website about schools in the Victorian period is at http://leicester.omeka.net/exhibits/show/victorianschooldays/schoolbuildings

The period opens with the Education Enquiry of 1833, published by parliament as an abstract of returns in 1835:

- Education Enquiry, Parl. Papers 1835 (62)

The return establishes a bench mark for the historian, setting out the educational provision in every village immediately before a period of substantial change. Unlike the 1818 enquiry mentioned in the last section, although the questionnaires were forwarded to each parish’s overseers for the poor, there was nothing in the instructions saying that only those schools that educated the poor should be included. A direct comparison of the two returns therefore cannot be made. Additional questions were asked in 1833, including the ages at which children entered and typically left each school, how each school was funded and whether the schools were confined to children from one religious denomination, but these questions were rarely answered. It is no coincidence that this enquiry followed hard on the heels of the great Reform Act of 1832, which widened the parliamentary franchise and led to an increasing interest by government in ensuring all social classes had access to education.

It is apparent from the answers provided by many parishes that the number of schools was increasing. In the small village of Osgathorpe, for example, as well as the free school which had been established in 1670, there were three other schools, including one which had opened in 1825 and another which opened in 1832. A Sunday school had also been established in 1829. In Desford, the return tells us that new schools had opened in 1826, 1829 and 1833.

Endowed and Grammar schools, 1833-1870

If the two enquiries of 1818 and 1833 reveal that there was an endowed school in the parish, there are several other parliamentary papers which should be checked, and which will probably contain more details. These are available through University Libraries. The most useful (from quite a long list) are:

- Reports of the Commissioners of Charities, Parl. Papers 1839 (163) together with its Analytical Digest, 1843 (435).

- Return of Endowed Grammar Schools, Parl. Papers 1865 (467). This provides a summary of the endowment and any modifications subsequently agreed by the Court of Chancery, the names of the trustees, subjects taught, number of masters and how they were appointed, number of pupils split by age, number who had progressed to college, and any bursaries awarded.

- Report of the Schools Inquiry Commission, Parl. Papers 1867-8 (3966). This can contain a lot of detail and follows personal visits to each school by a parliamentary commissioner (see below).

The Charity Commissioners’ reports provide more information for the historian than just the bare details of the foundation of each school. Many of the entries give details of the subjects taught, information which is rarely available elsewhere, for example at Breedon on the Hill, reading, writing, arithmetic and needlework were taught, and at Long Clawson the children had lessons in English grammar, writing, arithmetic, geometry and mensuration. One of the best-known, and most picturesque, endowed schools in Leicestershire is the ‘Old Grammar School’ or ‘Free School’ at Market Harborough (above). The Charity Commissioners’ reports provide details of the original endowment of Robert Smith or Smyth, who established this school for 15 poor scholars of the Anglican faith, and of the two additional endowments by Christopher Shaw in 1618 and Thomas Peach in 1770. They also note that children from all religious denominations began to be admitted from 1823, and that the ‘recent establishment of a National School’ in the town had resulted in a decline in the number of pupils at the Free School.

The 18th and early 19th centuries were a difficult period for the traditional grammar schools, as the demand for lessons in Latin and Greek declined substantially. Parents from the rising middle classes who could not necessarily afford the fees of the larger private schools wanted their children to be taught subjects more suited to industrial and commercial life, or which would help them gain a commission in the army, or an appointment in the civil service. It was not just Market Harborough schools which was struggling. Some grammar schools had very few pupils, while other schools in the same town, or even in the same building, were almost full to overflowing.

Endowed schools were legally unable to step away from the documented wishes of their founders, a point confirmed at law in a case heard by Lord Eldon in 1805. In the case of grammar schools, it is worth looking for

- Court papers at The National Archives, or parish copies of such papers at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland to see if permission to vary the curriculum was sought. If permission was granted, details will be in the Return of Endowed Grammar Schools already mentioned.

The Grammar Schools Act of 1840 provided some flexibility by allowing endowments to be used to teach other subjects. For the background and some details of local cases, those tracing the history of an early grammar school should also read:

- B. Simon, ‘Local grammar schools, 1780-1880’, in B. Simon (ed.) Education in Leicestershire, 1540-1940 (Leicester, 1968)

The Report of the Schools Inquiry Commission mentioned above (also known as the Taunton Commission) sets out within a table the findings of a major investigation into endowed schools. For each school it provides the name of the donor(s), the date of the school’s foundation, the endowment income, whether there was a house for the master, the weekly fee for pupils, the predominant occupation of the parents, separate numbers for male and female pupils, whether board and/or clothing was provided, any advanced subjects taught (such as Latin, natural sciences or algebra), the number of scholars apprenticed, the number of trustees, the number of teachers, their qualifications, their mode of appointment and whether or not the school fell within the government inspection regime (described below). Tabulated information allows schools to be compared, and the full reports give a good flavour of the school, revealing information that would not be available elsewhere. For example, the report on the school at Ashby de la Zouch records that the school had two departments, one ‘on the level of a National school’ with 160 boys on the register, ‘but during six years only eight boys had passed from it to the upper [school] … The boys of the two departments turn into the playground at different times, and are never allowed to mix together. Those in the lower are mostly sons of small tradesmen or skilled artisans … Those in the upper department are chiefly sons of the better tradesmen and professional men of the town and neighbourhood’. Most of the boys in the upper school went on to university.

The recommendations of the Taunton commission, and their implementation, did not start to take effect until the 1870s, and will therefore be considered below.

Voluntary and subscription schools, 1833-1870

Government grants became available from 1833 for up to half the cost of building schools for the children of the labouring classes, provided those new schools were affiliated to either the National or the British Society and, if they were non-denominational, that the school timetable included a daily Bible reading. This encouraged the building of new schools and affiliations to one of the two major voluntary societies, and in some places these schools crowded out existing private schools, which were unable to compete.

- Trade directories provide a useful source of information about schools in this period, and many are available online. It is worth looking at one directory for each decade, especially those published by William White or Kelly

- National School files contain applications for grants from the National Society, and are held at Lambeth Palace Library.

- The British Society Archive, which includes correspondence with individual schools and details of grants awarded, and is held at Brunel University.

- Details of government grants are held at The National Archives, and can be found in class ED103

- School plans – many are held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland

Grant applications include details such as the average attendance, other schools in the parish, the dimensions of the new building and the cost of the building and land. Clergymen applying to the National Society were asked to outline any ‘special circumstances’ relating to their application, and many wrote a page or more about the social character of their parish, economic conditions, the extent of nonconformity and the difficulties of raising money for a school. When the building was complete and immediately before the grant was paid, an account had to be filed, showing the cost and how the money had been raised.

In 1839, Government inspectors were appointed to visit all schools receiving a grant, but with only two inspectors appointed to cover the whole country (until 1843), the system was neither rigorous nor effective. Diocesan education boards were established the following year, and religious inspection introduced to all National (i.e. Church of England) schools. This system of dual inspection by the state and by the religious authorities continued until 1870. From 1840 it was no longer necessary to be affiliated to one of the two major voluntary societies to qualify for a government grant, and other denominations began to establish schools of their own. Castle Donington, for example, had both a Baptist and a Methodist day school by the mid 1840s.

Two schemes were introduced to improve the quality of the teaching. From 1844, the government provided funding to teacher training colleges. There was also a recognised need to replace the monitorial system of teaching for all but the youngest children. Although economical, the system gave rise to a continual need to train new monitors, as they were simply older children who could leave without giving notice when they found work. In 1846, a pupil-teacher scheme was introduced and the government also began to provide regular grants to help with teaching costs. Pupils aged 13 or over who passed an examination before a school inspector could be accepted on to the pupil-teacher scheme and would serve a five-year paid apprenticeship. They would be required to teach for 5½ hours each day and would receive 7½ hours instruction each week. During their apprenticeship they were examined annually by government inspectors, and on satisfactory completion they became eligible to compete for a scholarship for a three-year training course to become a certificated teacher. Whereas monitors were often the children of labourers, few working-class children became pupil-teachers, as they could not afford to remain at school until they were 13.

A survey carried out in 1846-7 by the National Society of all Anglican school provision in England and Wales (both day and Sunday schools) contains statistical information about attendances, costs, security of tenure and often some comments about the adequacy of provision. This was one of several surveys carried out by the Society, and is the most detailed of them all.

- National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church, Result of the Returns to the General Inquiry made by the National Society, into the state and progress of schools for the education of the poor … during the years 1846-7, throughout England and Wales ( London, 1849).

With the increase in daily schools, the role of Sunday schools in providing basic education is now diminishing, although they remain important and popular institutions until well into the 20th century.

- The 1851 Ecclesiastical census gives details of Sunday school attendances (both Anglican and nonconformist) on 30 March that year. The files of returns from each registration district is available as a free download from the National Archives (search for ‘ecclesiastical census’ followed by the name of the registration district.

Until 1862, the annual teaching grants were paid directly to the master and to the pupil-teachers, the latter receiving £10 at the end of their first year, increasing by £2 10s each year provided they passed their annual examinations, to reach £20 at the end of their apprenticeship. By 1856, around three-quarters of all children at school were being taught in a school that received a grant.

The cost of these schemes was substantial, and as school was not compulsory it was not necessarily reflected in higher literacy rates. A parliamentary commission (the Newcastle Commission) was established, investigated and reported back, and in 1859 a revised scheme was drawn up which applied from 1862. Grants became conditional upon the following criteria being met:

- a register and log book had to be kept, recording attendance and brief details of teaching and attendance

- the school had to employ a certificated teacher (although from 1867 schools in rural areas were permitted to share a certificated teacher)

- the girls had to be taught needlework

- the school building had to meet minimum specified standards, including a requirement of 80 cubic feet of space per child, based on the school’s average attendance, as fresh air and good ventilation were seen as important for good health. Of course it was cheaper to build upwards than outwards, which would have required more land, hence the height of many Victorian classrooms. Tall rooms also allowed the windows to be set at a level that would prevent the children becoming distracted by events outside

- there had to be two daily sessions, each of at least two hours (for most schools this would be satisfied by a morning session and an afternoon session).

Subject to meeting these requirements, the amount of the annual grant was dependent upon a combination of the school’s average attendance, the actual attendance on inspection day and the performance of the pupils examined by the inspector. The rates changed from time to time, but in 1862 a flat rate grant of 4s (20p) was paid for each pupil, based on average attendance over the year. Children over 6 years who had attended for the equivalent of at least 100 days over the year could be entered for examinations in reading, writing and arithmetic, and would earn the school a further 2s 8d (13p) for every pass. There were no examinations for infants, but an additional grant of 6s 6d (32½p) was paid for every child under 6 years who was present on the day of inspection, provided they were taught in a manner which would not interfere with the lessons of the older children. A second classroom for infants was becoming a necessity. Bribery to ensure attendance on inspection day was not unknown.

New records therefore become available from 1862, and provide information on the day-to-day life of the school, and many of these documents have been deposited with the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland. These include:

- Attendance registers

- School log books – one of the most interesting and informative types of school record, but there is no requirement for them (or any other type of school record)n to be deposited. If there are no log books fro your school at the record office, it is worth asking the school headmaster and secretary if they are still on the school premises.

- Inspection reports (and if these don’t survive, there will usually be a summary of the comment made within the log book)

Although the grant was now paid to the school rather than to individual teachers, many schools gave all or part of the teaching grant to their staff. This introduced a form of performance-related pay. Although a hot political topic today, it seems to have been accepted without demur by the teachers of the 1860s. Strategies were adopted by teachers that would maximise their personal reward. Key to this was attendance, and log books record what was clearly an uphill struggle for many schoolmasters and mistresses. Children were regularly kept off school to earn a few pence to help the family budget, or because of poor weather, especially if they had a long walk, poor footwear and no coat.

In Queniborough we learn that on 20 April 1866 ‘Anne Elizabeth Kilby [was] kept at home to seam socks’. With one eye on the additional grant the school could receive, in November 1871 Queniborough school began to offer cash prizes for good attendance, and in 1874 the school promised ‘6d to every child who attends 36 times in one month’, mornings and afternoons counting as separate attendances. In the first month 23 village children had earned their cash reward. Again, it was a matter of strategy and tactics. It could be worth paying 6d (2½p) to gain an extra 4 shillings, but only if that didn’t involve paying too many sixpences to children who would have attended anyway.

The grant could be reduced at the discretion of the inspector if the teaching or school discipline was judged to be poor, or if there was a shortage of furniture or books.

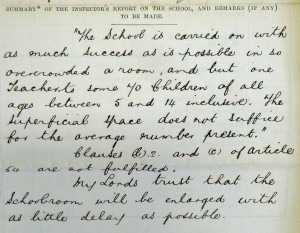

The inspection report for Groby Church of England School for 1869 suggested that a separate classroom should be built for the infants and first standard, who could be taught by a monitor. The following year nothing had changed, and their report comments, ‘The School is carried on with as much success as is possible in so overcrowded a room, and but one Teacher to some 70 Children of all ages between 5 and 14 inclusive.’

Elementary Education, 1870-1902

Forster’s Education Act of 1870 was the first step on the path to compulsory education for all children. It divided England and Wales into school districts (mostly civil parishes) which had to provide enough school places for all the children living there. How these were provided was very much a political ‘hot potato’. The Act allowed a new type of school to be established – a non-denominational board school, funded by ratepayers, financed by borrowing and managed by an elected board of between 5 and 15 members, chosen every 3 years by the ratepayers. If nothing was done, the Privy Council would impose a new board school on the district.

Building grants were abolished by the Act and remained available only to the end of 1870. What followed was a flurry of school building by patrician landowners keen to take advantage of the last few grants, in order to avoid the establishment of a management board which they might not be able to control, and to retain a strong connection between the local school and the Anglican Church. In some villages, such as Groby, a new and larger school was provided by a wealthy landowner, while in others, such as neighbouring Ratby, the local preference was for a ratepayer-elected board to provide and run the school, with money for the building borrowed from central government.

Most Anglican clergy, and many parishioners, were strongly opposed to Board schools, especially if a board would replace a small school with a strong Anglican ethos or where it was feared that rates would rise substantially. In contrast, many nonconformists welcomed the provision of non-denominational education through a ratepayer-funded board school. This could cause major tensions within a village, and impact on the ability of an Anglican clergyman to raise enough cash locally to provide any additional school places that were required, or any building improvements requested by inspectors.

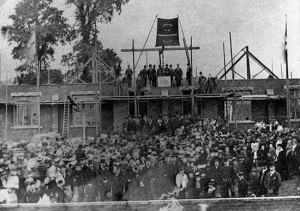

Nonconformity was strong in Sileby, and there were separate Sunday schools for General Baptists, Wesleyan Methodists and Primitive Methodists. Many parents might not have been keen for their children to attend a day school where they could be taught the Anglican catechism. In 1879 local businessman and philanthropist Thomas Caloe provided ‘the inhabitants of Sileby’ with a non-denominational day school. According to the local vicar, their aim was ‘to crush out our National School ‘. The photograph was taken at the stone-laying ceremony, and the banner wishes ‘Success to the Undenominational Schools’. The church school could not be crushed so easily, and by 1884 the managers of the ‘Undenominational School’ in King Street wanted to hand it over to a board. The school is still there today, although it is now owned by the council and is known as Redlands Community Primary School.

Essential sources for the 1870s include:

- Trade directories

- Newspaper reports. As this was a very political controversy, with Tories generally preferring an Anglican school and Liberals pushing for a Board, different views of the debate may be reported in each of the county’s two newspapers, the Leicester Chronicle (Liberal) and the Leicester Journal (Conservative).

- Grant requests (as listed above), especially correspondence sent to the National Society with grant applications

- Parliamentary papers concerning votes for boards and numbers of board schools

- Minutes of meetings of school managers and of the first boards

The new board schools established in towns were very large, but around half of all board schools were established in parishes with fewer than 500 residents, perhaps because the church school was unable to expand due to a lack of money, or because the parish contained many nonconformists who preferred a board school. Board schools could charge no more than 9d. per pupil per week, but often charged less to match the fees of local schools affiliated to the National Society, many of which only charged 1d. or 2d. per child per week. Unlike church schools, board schools were able to cover the fees for poor children from the rates. They also had the option to pass by-laws making attendance compulsory, and could appoint an attendance officer to enforce this. Some boards established a tiered system with full time attendance compulsory up to the age of 10, for example, followed by compulsory part-time attendance until a certain standard had been passed. From 1876, school attendance committees had to be established to cover all schools, although where there was no by-law, attendance was still not compulsory.

Compulsion was finally introduced for all schools under the 1880 Education Act, and the number of Standards was increased to seven. Children had to attend full time between the ages of 5 and 10, and then had to continue part-time, attending 250 half-days each year to the age of 12 and then 150 half-days annually until they were 14 unless they had passed the Fifth Standard. It was enforced through certificates of education, which had to be seen by employers. Weekly charges continued (they were not formally abolished until 1918), but an additional grant was payable to schools from 1891 if they abolished all fees from parents. From 1893 full-time attendance became compulsory to age 11, and then to age 12 from 1899.

The Anglican battle to maintain control of the village school did not end in 1870. Although the population of many rural parishes fell as people migrated to the towns, parts of Leicestershire with strong manufacturing, mining or quarrying interests saw population growth. Increases in the school leaving age also added further year groups. The number of school places required therefore continued to increase in some villages. Additionally, pressure to improve school premises increased, especially where there were just one or two rooms, and if money could not be raised to cover the costs, a board would be the inevitable result. The following sources continue to be useful for this period:

- Log books and inspection reports (at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, or often still held locally) continue to be important sources in this period

- Government parish and school education files at The National Archives (class ED).

- National school files at Lambeth Palace Library.

- Board school minutes at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland

- Managers’ minutes for voluntary or subscription schools at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland

- Local newspapers.

- There are also numerous parliamentary papers concerning schools in this period, with many containing figures relating to school income and expenditure, almost on an annual basis.

Endowed schools, 1870-1902

Because endowed schools stemmed from individual acts of charity, they were unevenly distributed, sometimes in places that were not especially populous. The Taunton Commission of 1867-8 proposed a complete restructuring of the educational provision they offered, with three grades of school, broader curricula, increased provision for girls and changes to the inspection and examination regime. The Endowed Schools Commissioners were established by statute in 1869 to initiate new schemes and bring these recommendations into effect. The key question in respect of any individual endowed school is therefore how it was affected.

The Endowed Schools Commissioners sought to reach agreement on a county-by-county basis to creating three grades of school, according to whether children were expected to leave at age 18, 16 or 14, with curricula aligned to that leaving age (and effectively to social class). There was much political debate about which children should be admitted. Most endowments had been intended for the children of the poor, but some argued that this income should now be directed to benefit the ‘middle classes’, as the 1870 Education Act provided ample places for poorer children. The Commissioners also had to work within a framework of existing school buildings and locations which were not necessarily ideal, and endowments that raised vastly different sums from one place to the next. That required an element of merging and re-apportioning endowments between schools within a county, even though that could disadvantage people in some localities and broke with the wishes of the original donors. There were also concerns locally about the proposals for the election of new governing bodies for these schools.

In Leicestershire, a county meeting was convened in May 1871 under the chairmanship of the sheriff, and led to the formation of a committee to consider all options before the government commissioners visited. Rev. J.H. Green, master of Kibworth grammar school, was the secretary to the county committee and he provided a flavour of the views of some Leicestershire people to a parliamentary select committee, which can be read in:

- Report of the Select Committee on the Endowed Schools Act, Parl. Papers 1873 (254)

- Newspaper reports

By 1874, when the functions of the Endowed Schools Commissioners were transferred to the Charity Commissioners, new schemes had only been established for around one-third of all endowed schools. Their proposals in Leicestershire are set out in:

- Endowed Schools and Charities: copy of schemes and suggestions, Parl. Paper 1874 (203)

The Commissioners sought to establish for two first grade schools (for children to age 18) and six second grade schools, with the other endowed schools becoming third grade schools. However, the Endowed Schools Act of 1873 had allowed alternative schemes to be drawn up where an endowed school provided elementary education, provided aggregate income over three years did not exceed £100, and several county schools took advantage of these provisions.

- Details of schemes agreed under the 1869 or 1873 Endowed Schools Acts may be found in parliamentary papers or parish records (perhaps deposited at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland ).

In Thurcaston, for example, a scheme of 1875 (under the 1873 Act) resulted in the conversion of an endowed charity school into a public elementary school under a new board of governors with four elective members and three ex-officio clergy governors. The income from the endowment could be used by the school in accordance with the objects set out, which included the provision of a lending library, maps, scientific apparatus and gym equipment as well as providing free places to ‘meritorious scholars’ (with no mention of gender). The scheme, as first drafted, also set out that the teacher was required to play the harmonium or organ for Sunday church services when called upon to do so!

Private schools

There are very few records that survive for private schools and the only sources are often:

- Newspaper advertisements

- Trade directories

- Census (for schoolteachers, although it is possible they taught at a school in another town or village)