Some knowledge of the features and dates of the main architectural periods is useful for understanding not just the history of a parish church but also aspects of the history of the town or village where it stands. The date of the church’s construction and the date of any major alterations to the fabric can point to periods of wealth in the local economy, or the arrival of a new wealthy family or advantageous marriage by the lord of the manor, and sometimes also to periods of growth or decline in the parish population. Assigning dates to the beginnings and ends of architectural periods, especially on a local basis, is not an exact science. Limited building records survive, there were transitional periods between styles and the adoption of new styles depended on the transmission of ideas and techniques from other parts of England or the continent, on the receptiveness and abilities of local craftsmen and the wishes of their patrons. However, some parameters are essential if we are to make any sense of what we see. Architectural historians broadly agree on the following dates for each of the principal stylistic periods (give or take a decade or two at either end, for the reasons above):

Saxon pre 1066

Norman 1066-1190

Early English 1190-1290

Decorated 1290-1370

Perpendicular 1370-1540

Renaissance/Classical 1540-1840

Victorian/Gothic revival 1840-1900

20th century from 1900

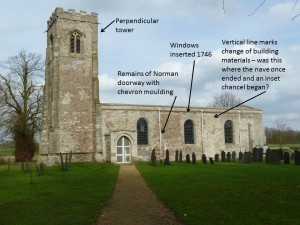

Nationally, the Perpendicular style is prominent among medieval churches, partly because it ran for longer than the other styles, partly because the late 15th and early 16th centuries were periods of greater prosperity, when earlier architecture was replaced, and partly because a lengthy lack of interest in building or rebuilding churches following the Reformation meant that this style of architecture tended not to be replaced until the mid 19th century. In much of Leicestershire, the Decorated style is also common, despite this being the most short-lived of all the medieval styles and despite the arrival of the Black Death in 1349, which would have badly affected building projects. Many of the county’s churches have at least one Decorated feature, and in some cases it is of the finest quality. Who could fail to be impressed by the south-western corner of Gaddesby church, for example? We should not be surprised that features like this were never replaced, but the impression still remains that this was a period of peak wealth, and that after the 14th century many parishes did not have much money to invest in their churches.

Windows are one of the easiest features to date (as is evident in housing estates across the country), although they do not necessarily date the wall. As building techniques improved, allowing larger openings, and as glass became more widely available, windows got larger, and new windows might be inserted into an older wall to let in more light. Conversely, if an expanding population resulted in the addition of an aisle, the old doors and windows were likely to be retained and used in the exterior walls of the new aisle.

The top of Saxon windows may be triangular, when masons had little experience of working with stone, or semi-circular. They can be narrow but deeply splayed and set into very thick walls, letting in as much light as possible through such a narrow opening. Norman windows have a semi-circular head, and by the later Norman period those that survive may have richly carved mouldings, often in a chevron pattern, such as those shown above.

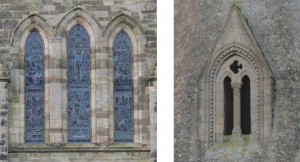

The Early English period saw the round arch replaced by the pointed or Gothic arch. Single and grouped lancets are the first forms to appear, as seen at Breedon on the Hill, followed by plate tracery, where twin lancets are placed under a single moulding which directs the rain water away from the window, and the space between the lancets and the moulding is pierced by a smaller opening (above). By 1300 the stonework dividing groups of two or more lancets had become a thin mullion and Y-tracery or intersecting-tracery was created, as seen at Cossington (below).

These larger windows encouraged creativity, and by the middle of the Decorated period many different kinds of tracery had developed. The most common of these in Leicestershire is a regular lattice known as Reticulated, and at least one Reticulated window can be seen in a high proportion of the county’s churches. There is a reason why this period has been termed Decorated. Architecture becomes flamboyant, with many different kinds of carved mouldings appearing around doors and windows and inside churches, on piscinas, sedilia, fonts and the capitals of pillars. Pinnacles appear, as decorative features when used inside the church, around tombs or on a font, but also serving a functional purpose when coupled with buttresses outside.

The Perpendicular period sees windows become larger still, and as the period progresses the arches flatten out or are replaced by a straight top. The mullions in Perpendicular tracery extend from the bottom of the window up to the top, with the top section usually forming a series of panels shaped like open books, ideally suited to carry stained glass images. In the wealthiest churches there will often be more window than wall. A clerestory was often added in this period, letting more light into the church and illuminating the rood above the chancel arch. Usually there will be one window for every bay of building, but in wealthier parishes there could be two clerestory windows to each pay (best viewed inside).

The Renaissance or Classical period saw a return of the round arch, both in the windows of houses and churches, as seen at St Wistan, Wistow (below), a medieval church that was substantially remodelled in 1746. Not every church built in this period followed this new style, and greater variety was seen, including versions of Gothic at Holy Trinity, Staunton Harold (1662-5) and the exterior of St John the Baptist, King’s Norton (1760-75). Churches built in this period are generally far easier to date, as there will be surviving documentary evidence for many of them.

Victorian architects drew on the full range of Gothic styles, sometimes creating true replicas, but at other times creating variations of their own. The truth can usually be discovered from documentary evidence, by close examination of tooling marks and the edges of tracery, by the degree of weathering, and also by looking at the engravings of the pre-Victorian church which can be found in John Nichols’s History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester.

Interior features can also be dated by their style, although this requires a more experienced eye. Until you become very familiar with the different styles it is best to rely on a guide such as the Leicestershire volume in the Pevsner Buildings of England series. As with the outside of the building, you should focus on scars to the fabric, indicating changes, the degree of uniformity of style, suggesting peak periods of wealth or building activity and the degree of elaboration within a style.

Back to Reading the building

Or move inside to the chancel