The closer you get to the present day, the more records there will be to look at, through increasing bureaucracy, legal changes, cheaper paper and better document survival. The documentary sources available to you will be considered under the following headings:

Religious Life; Worshippers; Clergy; Clergy income; Modern parish life; Building

Religious life

Some of the most valuable documents for this period were create by and for the regular visitations conducted by bishops and archdeacons.

The visitation of Bishop Sanderson of 1662 follows hard on the heels of the Act of Uniformity that required all clergy to conform to its requirements by August 1662 or be ejected from their livings (at which point they became known as nonconformists). At the same time, survivors among the royalist or high church clergy who had been ejected during the civil war were looking for benefices. Sanderson was seeking to ensure compliance with the Act of Uniformity and the new prayer book of 1662 (that is still in use in some parishes today). The records are a mixture of Latin and English. Some of the entries mention deliberate damage to the building during the civil war or the lack of a font (probably removed in accordance with a parliamentary ordinance of 1644), while others mention the failure of clergy to use the prayer book. The records have been published in four parts:

A.P. Moore, ‘The primary visitation of Robert Sanderson, Bishop of Lincoln, in 1662, for the Archdeaconry of Leicester’, The Antiquary (June, October, November and December 1909)

Bishop Wake, appointed to Lincoln in 1705, introduced a questionnaire for completion by all incumbents in the diocese, which included questions about religious observance and nonconformity in the parish and the provision of schooling. His successor Bishop Gibson continued to use the same system. The original responses to Wake’s questions from 1706, 1709, 1712 and 1715 are held at Christ Church, Oxford, but have been published in two volumes (the second of which contains the details from Leicester Archdeaconry:

J. Broad (ed.), Bishop Wake’s Summary of Visitation Returns from the Diocese of Lincoln 1706-15 (Oxford, 2012)

Gibson’s printed forms from 1718 and 1721 with their written replies are held in St Paul’s Cathedral library, but there are microfilm copies at Lincolnshire Archives.

Moving on to the end of the 18th century and the early 19th century, three very good and very legible sets of visitation records created by Archdeacons Bickham, Burney and Bonney are held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, and are an essential source for the history of your church. Bonney’s records are particularly full, and run to several pages for each parish. The findings of Bickham and Burney have been summarised in two articles, which are useful for background and a brief comparison of parishes, but you should look at the original books for any individual church study, as they will hold more information.W.A, Pemberton, ‘The parochial visitation of James Bickham D.D., Archdeacon of Leicester, in the years 1773-1779’, Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society, 59 (1984-5), pp. 52-72.

Visitation records for the period between 1846 and 1921 are held at Northamptonshire Record Office, and take the form of separate questionnaires to churchwardens and to incumbents. Those addressed to the incumbents are the most informative, and will not only tell you about the congregation and any church groups (such as Bible study meetings), but also have a section in which the incumbent can raise any issues he wishes with the bishop. When an incumbent took up this opportunity there can be some very candid remarks about social issues in his parish and the challenges he faced in his ministry.

Church court records can also be informative. Those for Leicester Archdeaconry have been indexed, and there is both a binder and a CD at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland giving details.

Worshippers

The Compton Census of 1676 takes its name from Henry Compton, then Bishop of London. We do not know precisely why it was taken, but it seems to have been originated by government rather than the church, and was perhaps intended to demonstrate to the king that the majority of the people were loyal Anglicans. Incumbents were asked to provide details of the number of conformists, recusants and dissenters within their parish. For the details collected see

A. Whiteman, The Compton Census of 1676: A Critical Edition (London, 1986)

For the mid 19th century, the ecclesiastical census of 1851 (the only full religious census ever to be held) provides information for most parishes on the church dedication, income, the number of appropriated and free seats, the number who attended each service on Sunday 30 March 1851 and how many attended Sunday School. The census was ordered by Parliament, not the ecclesiastical authorities. It was intended largely to find out whether there were enough churches, whether they were in the right places and whether there was enough accommodation within them for the population. A number of Anglican clergy failed to complete the forms, and it is known that some feared it would show their church in a poor light. Some of these missing forms were replaced by brief summaries of information provided by civil registrars and others, while other churches were not included at all. The census returns can be found on microfilm at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, or are available as a free download from The National Archives. To download the file (which could be as large as 100Mb), first identify the civil registration district that your parish falls within and then search The National Archives catalogue for ‘ecclesiastical census’ followed by the name of the registration district. You will need to register, add the file to your basket and checkout, but there is no fee to pay.

Parish magazines and vestry minutes can be voluminous and are not very rewarding to search unless knowledge of a particular event from another source allows you to focus on a specific date.

Clergy

Details of ejected ministers, and those who resigned or were forced to move between 1660 and 1662 can be found in:

A.G. Matthews, Calamy Revised being a Revision of Edmund Calamy’s Account of the Ministers and Others Ejected and Silenced, 1660-2 (Oxford, 1934).

More generally, a useful book on many aspects of the clergy and religious life in Leicestershire in the years following the Restoration is:

J.H. Pruett, The Parish Clergy under the Later Stuarts: The Leicestershire Experience (Urbana, 1978)

One of the key questions in this or any other period is who owned the advowson (the right to present new clergy)? Did they choose graduates or family members? Many advowsons were sold in this period, until this was prevent by Act of Parliament, following which sales could not be made after the first two presentments had been made after 1924, although ownership of an advowson could still be transferred as a gift. Until 1800, details of the patronage of a church will be found in John Nichols’s History and Antiquities of the County of Leicester, and his lists are generally accurate. From the mid 19th century until 1926 annual lists of clergy and their patrons were included in The Peterborough Diocesan Calendar, Clergy List, and Almanack for the Counties of Leicester, Northampton and Rutland. From 1926 the equivalent volumes for the new Leicester diocese were Leicester Diocesan Calendar, Clergy List and Year Book; Leicester Diocesan Directory (latterly the Diocese of Leicester Directory), although lists of patrons no longer appear in the most recent issues. During the 20th century many advowsons were purchased by, or otherwise came into the hands of, the newly constituted Diocesan Board of Patronage, and will remain there, the only complication being if two benefices with different patrons merge, when the patrons will usually present in turn. A register of patrons was established nationally in 1986, and is held by the diocesan registrar, but the current churchwardens (and incumbent) should know the identity of the present patron of your church.

The Clergy of the Church of England database provides brief details for many clergy between 1540 and 1835. Alumni Cantabrigienses and Alumni Oxonienses are also valuable sources of biographical information. Details of clergy in the early 18th century are included within:

W.G.D. Fletcher, ‘Some unpublished documents relating to Leicestershire preserved in the Public Record Office’, Reports and Papers of the Associated Architectural Societies, 2 (1893-4), pp. 227-365

Clergy income

Income varied widely from benefice to benefice, for no reason other than accidents of history, as the extent of glebe land held depended on gifts made to the church in the medieval period, likewise whether the clergyman was entitled to receive the valuable great tithes or not (in other words whether he was a rector) depended on whether the church had been given to a religious house. Income was important, as a strong income could attract the best educated candidates with good pastoral skills, although in the hands of some patrons the living could also go to a non-resident pluralist who had made good connections.

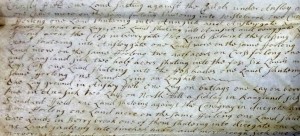

Until 1978, an incumbent’s overall income came from a mixture of income from glebe land, tithes, fees and possibly a stipend. The most important factors were the status of the living and whether it was held in plurality with another. Today the words rector and vicar are used more or less interchangeably, and if there is any differentiation it is usually on the basis of seniority or time served. Historically there was a vast difference. The rector was entitled to receive all the tithes of the parish, but a rector who was not a clergyman (as rectors could be monasteries or, after the Reformation, lay people) had to appoint a vicar to take services and provide pastoral care. The vicar was paid by the rector, typically being given the less valuable tithes and those that were difficult to collect, for example on new-born livestock, eggs, honey and garden produce. The other class of clergy were curates, who were usually appointees of other clergy, performing the duties in exchange for a stipend. A few churches were donatives – private churches outside the diocesan hierarchy, where a curate was directly employed and paid by a patron. The status of the living will appear in the Valor Ecclesiasticus (see Documents: Middle Ages and the Reformation) and in the assessment lists drawn up in connection with Queen Anne’s Bounty (see below).The appointment of curates by other clergy had to be approved by the bishop, who would grant a licence for absence. The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland has a card index of the licences they hold. In 1835 parliamentary commissioners were appointed to investigate church income and pluralities. Their report revealed, for example, that the rector of Cadeby in Leicestershire also held appointments as rector in Norfolk, in Suffolk and as vicar in Nottinghamshire. In 1838, legislation was passed to prevent a second appointment from being taken unless the churches were within ten miles of each other and the parishes met certain population criteria. Subsequent legislation further tightened these restrictions.The extent of glebe land was set out in a document known as a glebe terrier (see above), and could range from less than half an acre to over 1,000 acres. The figure might be in acres (not necessarily of standard size) or yardlands (a yardland was in the region of 30 modern acres, but varied in size from parish to parish according to the quality of the soil), or just given as a number of strips in the open fields. Glebe terriers were produced on a regular basis from 1571 until the early 19th century, and most parishes will have four of more surviving terriers either at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland (as original documents or on microfilm) or at Lincolnshire Archives.

From 1698 glebe terriers were required to include tithe customs and some give very detailed accounts of what was due. Tithe disputes were frequent, and would be heard in the church courts. These papers have been indexed in a purple binder at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, and the index is also on CD 40, held behind the counter. If parish copies of the papers have been deposited, they will appear in the parish binder listings. Disputes can also be mentioned in the tithe files of the 1830s, 40s and 50s at The National Archives. Fees payable by parishioners, for example for baptisms, marriages or burials, and fixed sums payable at Easter will often also be set out in glebe terriers after 1698.

The amount of glebe land did not remain constant. Tithes were often commuted if the open fields were enclosed by Parliamentary Act and award and a parcel of additional glebe land awarded to the church in lieu of future tithes. This will be mentioned in the award. Any money received as a result of an augmentation by Queen Anne’s Bounty was probably also invested in glebe land, although a tight market often meant it could be many miles away from the parish. Then in the late 19th century, as a result of the agricultural depression and falling rents, the Glebe Lands Act of 1888 allowed a parish to sell glebe lands and reinvest the proceeds in other assets, notably government stock. Such sales can be hard to trace, other than through declining figures being quoted for glebe land in trade directories, which are not always accurate. Any remaining glebe ceased to belong to individual incumbents from April 1978, under the Endowments and Glebe Measure of 1976. Glebe held by Leicestershire churches became vested in the Leicester Diocesan Board of Finance, even if the glebe land itself was situated in another diocese.

The issues for the church in the 18th and 19th centuries were not just that there were wide variations in benefice income, which bore no relationship to the area or population of the parish, but that too many parishes had income levels that could not support a clergyman and his family. In an attempt to alleviate the position, Queen Anne gave up her right to receive the clerical tax known as first fruits and tenths. From 1704, this would be paid to trustees and applied for the benefit of certain clergy with an annual income of no more than £50 (including curates from 1715). The Queen also agreed that all clergy with an income of £50 or less would be discharged from future payments of first fruits and tenths. The first step towards implementation was therefore to draw up a list of the 11,000 livings and the income of those that would qualify for augmentation, a task that fell to John Ecton, the Receiver of the Tenths. Several versions were published, and these show that around half of all livings had an annual income of £50 or less:J. Ecton, Liber Valorem et Decimarum (1711, 1723, 1728)J. Ecton, A State of the Proceedings of the … Bounty of Queen Anne (1719, 1721, 1725)

J. Bacon, Thesaurus Ecclesiasticus … (1788), a revised and enlarged version of Ecton’s Liber Valorem, produced by his successor

Ecton grouped the livings into separate categories. The bishops were asked to certify current income levels for those worth £50 of less per annum, which would become exempt from future payments of first fruits and tenths and eligible to receive the bounty.

Those which were not certified appear in his list as ‘livings in charge’, and were shown with the valuations and tenths given in the Valor Ecclesiasticus of 1535.

Those which had been certified were listed under the heading ‘livings discharged’. These showed the current income as certified by the bishop, plus the tenths figure (which was no longer to be paid) given in the Valor

In later editions there is a third category, ‘not in charge’ which are churches that were in the Valor but were found to no longer exist.

The assessment demonstrated the extent of the problem. there were around 5,600 livings eligible on grounds of income to receive the bounty, but the annual income from the first fruits and tenths paid by the other benefices was only £13,700, and as this tax was paid on the 1535 valuations carried out by Henry VIII, the revenue it raised would not increase over time. With augmentations of £200 each (in capital, to be invested in land to give an additional annual income of around £10), and many livings well under £50 so they could qualify several times, Ecton calculated that if no other money was made available it would take 500 years to bring all livings up to £50 – and of course the effect of inflation would mean that £50 would not suffice. To make the money go further, private benefactions were therefore encouraged by giving grants to eligible churches where the £200 bounty would be matched by a private donation of the same amount, with any remaining bounty money left allocated by lot, with the poorest parishes entering the draw first. From 1836 a benefaction had to be provided if a grant was to be made.

Between 1809 and 1819 Parliament also voted annual grants of £100,000 to the bounty governors, so more livings could be augmented, and larger sums started to be given. By then the £50 set a century earlier was considered too low. The clergy wanted benefices with income of less than £150 to qualify, which would create another 3,500 eligible livings. Parliament sympathised with the need to include more parishes, and in 1835-6 Ecclesiastical Commissioners were appointed and empowered to redistribute to poor clergy anywhere in the country the ‘surplus’ assets of cathedrals and bishops. After taking over these assets, their chosen method of distribution was by stipend to poor incumbents in populous parishes who had just one living. As a condition of assistance, they usual insisted on taking over the advowson, to prevent the patron receiving any benefit by selling this at a profit.

Clergy often applied to both schemes at the same time, but if the parish qualified for assistance from the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, the bounty governors would not help. In 1848 the two schemes merged to form the Church Commissioners.

There was also a local charity, Tobias Rustat’s charity for the augmentation of poor vicarages, which was active in parts of Leicestershire from 1688. Rustat had been vicar of Barrow upon Soar.

Records of augmentations include:

The valuations assembled by Ecton and Bacon mentioned above

C. Hodgson, An Account of the Augmentation of Small Livings by the Governors of the Bounty of Queen Anne, for the Augmentation of the maintenance of the Poor Clergy and of benefactions by Corporate Bodies and Individuals; with Practical Instructions for the use of Incumbents and patrons of Augmented Livings (2nd edition, including all augmentations and benefactions to the end of 1844)(London, 1845). This provides a list of augmented livings and the amount and donor of any benefaction given alongside

Parliamentary Papers, especially (a) those relating to Queen Anne’s Bounty, which include from 1814-15 regular lists of grants given, (b) the frequent reports to Parliament by the Ecclesiastical Commissioners (from 1835), (c) the list of benefices with income under £150 given in paper 1818 (005) and the return of benefice incomes in paper 1837(439)

Augmentation files for Queen Anne’s Bounty, held at Lambeth Palace Library. Search the online catalogue for references commencing QAB. Always use the ‘search catalogue’ option for this database and key the parish name into the top box, and not the place name box.

Augmentation files of the Ecclesiastical Commissioners, held at Lambeth Palace Library.

There may also be some documents at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland.

If your parish received an augmentation, you should also read:

Modern parish life

For a full history, don’t forget to consider parish life today. Talk to some churchgoers, attend a service yourself and look at the current parish magazine, newsletter and website (if any). Is today’s church high or low, or somewhere between? Does it use incense, the Book of Common Prayer or a more recent liturgy? Which version of the Bible does it use for readings? Are there any statues? What is the pattern of Sunday and midweek communion services? Could services be described as ‘happy-clappy’? Are there regular family services? What is the average age of the congregation? Is there a Sunday school? Will the parish accept female servers or a female minister?

Does the church play a full part in inter-faith/inter-denominational activities, e.g. ‘Churches together in …’

What groups are connected to the church, such as a choir, mothers and toddlers, etc? Does the incumbent have a close connection with the local school? Do other groups meet in the church or hire the building, e.g. community groups not connected with church, concerts, etc.

Has the benefice been united with any other(s) in recent years, or is it a team ministry? Does the current incumbent live in the parish? Have any non-stipendary ministers been appointed? The Diocesan Directory will provide basic information, and you may find more details on the church website. Other sources such as Crockford’s directory or advertisements in the Church Times are difficult to use without a date.

Other records listed in the parish binders vary widely from parish to parish, but can include building accounts, photographs of church groups such as the choir, and annual reports.

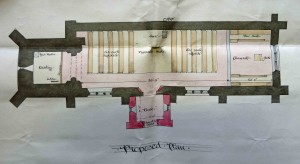

Documentary sources for the history of the building

A church rate had been introduced in 1661, collected from every resident of the parish according to their means, whether or not they worshipped at the parish church. It was used for the upkeep and repair of the building, excluding the chancel. The rate could be set at a modest sum, perhaps increased temporarily from time to time to pay for a specific project. As the proportion of the population who were Anglicans declined over the 18th and 19th centuries, the church rate became politically unacceptable, and it was abolished in 1868.

Almost every church carried out a large-scale restoration in the Victorian period. It was not cheap: restoration at Theddingworth cost £2,000 (partly because they chose a nationally-known architect) and at Ratby cost £3,500 (because the church had been allowed to become so ruinous that part of the building had collapsed).

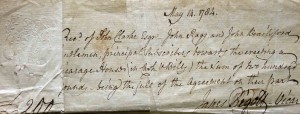

How extensive was the restoration, who was employed, how much did it cost and how was it funded? All or most restorations were paid for by subscription. The lord of the manor and the incumbent were often the main subscribers, and in some cases put up all of the money. In many cases there would also be funding-raising events and special collections. Some of the money may also have been borrowed, and the debt could take many years to clear.

G.K. Brandwood, Bringing them to their Knees: Church Building and Restoration in Leicestershire and Rutland, 1800-1914 (Leicester, 2002) includes a gazetteer of restorations. It is based on his doctoral thesis, which includes some further information

A number of Leicestershire churches were restored by the Goddards, and may be mentioned in

G. Brandwood and M. Cherry, Men of Property: The Goddards and Six Generations of Architecture (Leicester, 1990).

Trade directories can be very unreliable in respect of church architecture, but are a useful source for contemporary information about the church, such as the date and cost of restoration, and about other gifts made to the church, for example memorial windows or plate. By consulting one directory in each decade, you should be able to collect the pertinent information, although the details given may sometimes disagree with each other.

Newspapers and periodicals are another useful source for restoration projects, especially if you have a date, and can give details of fundraising events and of the services and celebrations held when a church reopened. Two useful bibliographies have been prepared, which can save you a lot of time searching for reports:

D. Parsons (ed.), A Bibliography of Leicestershire Churches, Part 1: The Periodical Sources (Leicester, 1978)

G.K. Brandwood (ed.), A Bibliography of Leicestershire Churches, Part 2: Newspaper Sources (Leicester, 1980)

The Associated Architectural Societies showed a keen interest in church repairs and restorations. Their brief reports are listed in part 1 of the bibliography mentioned immediately above, and the volumes themselves are on the open shelves under the issue desk at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland.

From 1818 the Incorporated Church Building Society made grants available for restoration or repair, usually conditional on all seating being freely available. But the grants were unlikely to be sufficient to pay for major renovation. Many of the records are at Lambeth Palace Library with others in the archives of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

There was also a Church Building Society for the County and Town of Leicester, established in 1838 and a national Church Extension Fund, set up in 1851.

If the church is listed, English Heritage will have an architectural description of the church in its current condition.

Don’t forget recent changes to the building, perhaps to suit the secular needs of the community, such as replacing pews with chairs, adding a kitchen area and lavatories. Annual reports to the parochial or district church council may include details of dates, costs, grants given and fundraising events held.

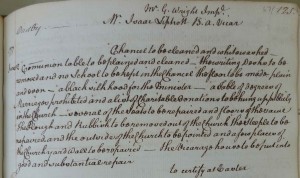

Every change made to a church building needed to be agreed by the church courts and a faculty issued, in a similar manner to the way in which planning permission is sought and given for other buildings. Parish copies of faculty applications may be held at The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, and will be listed in the blue parish binders. You may find other related documents there, including quotations for work that may or may not have been done to the building or the bells.