In 1849, Loughborough was the largest town in the county outside Leicester. It was a busy, bustling place, with a population of 10,170 in 1841, and a station on the Midland Railway. Nearly 1,500 new houses had been built since 1801. There was a weekly market, plenty of shops, and the main streets of the town were paved and lit with gas. Many people were employed making stockings or lace.

Map from the Public Health Inquiry, 1848

Unfortunately, employment and earnings in the textile industries were in decline, due to increased mechanisation and changing fashions. The rents on many houses were beyond the reach of the poor. Many lived in cramped houses, in courts off the main roads where several families would have to share a single ‘toilet’, which was no more than a seat over a cesspit. Water came from pumps and wells, sometimes at a distance from the house. With no adequate drainage, the ground where the well was sunk could be contaminated by human sewage. The Wood Brook flowed through the ceentre of the town, uncovered, accumulating waste on its way. Sickness and ‘fevers’ were common, and Death was a regular visitor to the home. One in five children died before their first birthday.

In 1848, a Public Health Act gave local people the power to elect a board of health for their parish, which would have the power to borrow money from the government to carry out improvements including laying drains and sewers, and supplying fresh piped water to all houses. Loans would be repaid through a tax on property (rates).

Under the Act, a government inspector would visit, report back to government and compel the parish to elect a local board of health:

- If the annual death rate exceeded 23 per 1,000 population, OR

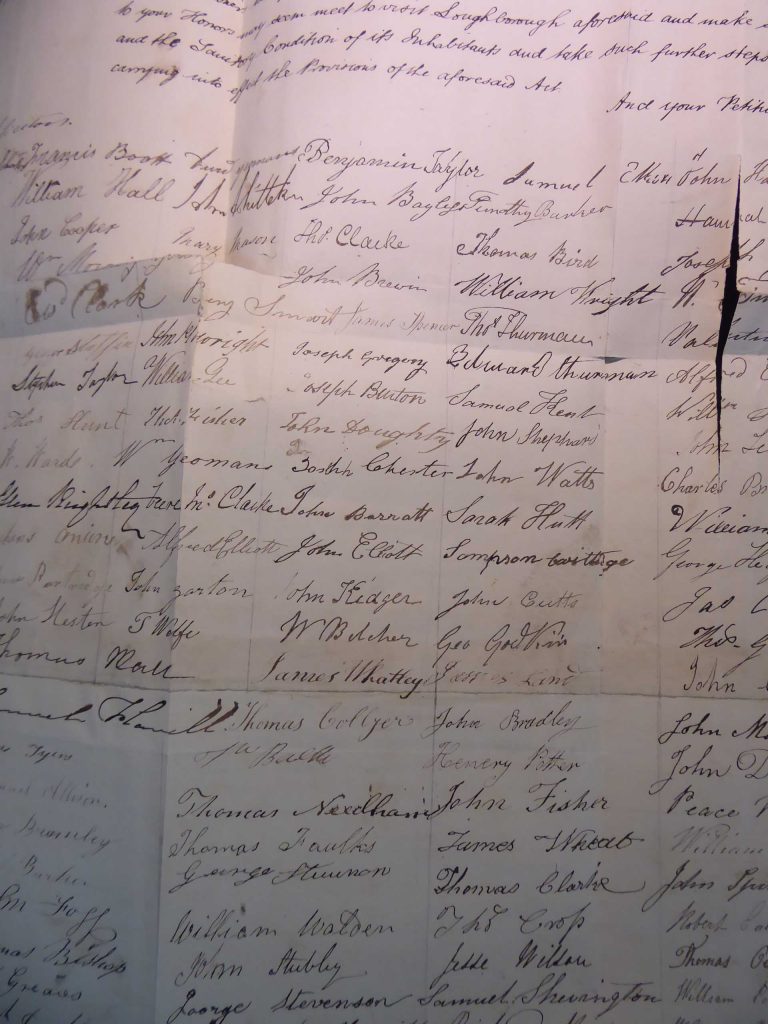

- If more than 10% of ratepayers signed a petition to the Board of Health in London saying they wanted a local board

In Loughborough, the death rate was 27 per 1,000 people AND 350 ratepayers (over 10%) had signed a petition asking for a government inspector to visit.

There was no choice. An inspector would call.