Enclosure was the process which converted communal open field land into small hedged closes owned by individuals, where villagers had no right of access. This guide will help you discover when and how the land within a parish was enclosed, and what records may survive to tell you more about the process.

When did enclosure take place?

In most parishes enclosure was not a single event, but a series of events spread across several decades or even centuries. Maps and written surveys (terriers) detailing strips of land laid out in the open fields frequently reveal closes of enclosed ground, perhaps near the parish boundaries. Although many Leicestershire parishes were fully enclosed following an Enclosure Act passed by Parliament, perhaps in the late 18th century, that was usually just the final and best-documented stage in a long process. Many earlier enclosures may have taken place but left few or no contemporary records.

Details of all known enclosures in Leicestershire were collected into two tables in the early 1950s and published at the end of the section on agrarian history in volume II of the Victoria County History of Leicestershire, on pp. 254-64 (not online). This volume can be found in some county libraries and in the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland.

These two tables are fully referenced with details of where to look for more information about the enclosures they mention. A few records of early enclosures have come to light since they were published in 1954, so check archive catalogues as there may also be other information.

The article preceding these tables provides an excellent introduction to the agrarian history of this county.

How was enclosure achieved?

Understanding a little about the process of enclosure will help you to identify and interpret those documents that have survived.

There were two main types of enclosure, by private action (with or without the consent of all landowners) and through an Act of Parliament.

Enclosure by private action or private agreement

Enclosures before 1488 are rarely documented, but for Leicestershire villages it is worth looking through George Farnham’s Medieval Village Notes (6 volumes published in the 1930s, with an index to the whole work in volume 6) for mention of ‘closes’ (enclosed fields). These volumes can be consulted in the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland.

Farnham’s ‘notes’ are transcripts from medieval records. These records for Brooksby, for example, transcribed in volume 6, include two legal cases brought by the lord of the manor, Richard Villiers, in 1388. One was against John Swayn for breaking Richard’s close, and the other was against Margaret Villiers (his step-mother) for ‘having made waste, sale and destruction of gardens, houses, lands, etc, in Brooksby’. John Swayn may have been trying to return a close to open field land, with Richard perhaps trying to blame his deceased father for the enclosures having been made (to avoid any personal penalty).

Between 1489 and 1598 it was illegal to remove land from the common field system to farm it privately. Legal inquiries were held in 1517, when evidence was heard about enclosures which had taken place since 1488. Transcripts of some of these records for Leicestershire (in the original Latin) can be found in volume II of I.S. Leadam, The Domesday of Inclosures, 1517-18 (Royal Historical Society, 1897).

More information about these and some slightly later enclosures can be found in a thesis by L.A. Parker, ‘Enclosure in Leicestershire, 1485-1607’ (PhD, University of London, 1948), which is available as a free download through British Library Electronic Theses Online. Parker identifies a peak of enclosure between 1490 and 1510, following which new enclosures fell away, before increasing once more in the 1580s and 1590s.

An Act of 1598 allowed lands in the open fields to be exchanged and merged by agreement. Most of these exchanges involved only part of the land in a parish, and only a few landowners. Agreements could break down if the parties fell out, or when one died.

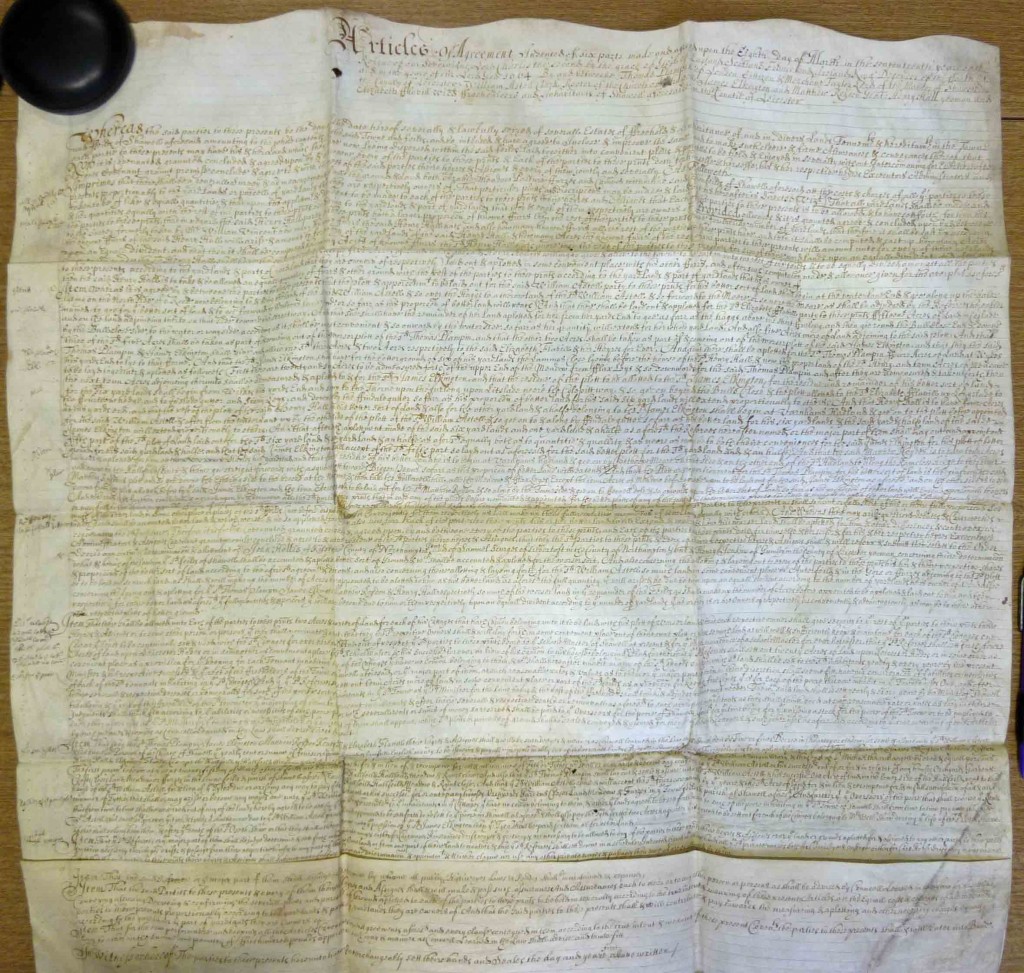

To minimise the risk of disputes or claims, articles of agreement were sometimes drawn up and executed by all parties, such as at Shawell (pictured). Surviving copies may have been deposited in the county Record Office. Those desiring greater legal certainty might choose to bring a collusive legal suit, resulting in a judgement enrolled with the Court of Exchequer or the Court of Chancery at Westminster, creating records which are held at The National Archives. Others deliberately avoided documentation, which would have involved legal costs.

Open revolt against enclosures broke out across south Leicestershire in 1607, following enclosure in Cotesbach. Parliament responded with a commission of inquiry. The commissioners’ returns have been published with an introductory essay by L.A. Parker, in volume 23 of the Transactions of the Leicestershire Archaeological and Historical Society (for 1947). They list 71 places in the county that had been affected by enclosure, and sometimes provide the date and the acreage involved, and the names of landowners.

Glebe terriers (written surveys of land in a parish that is owned by the church) can also provide evidence of the progress of enclosure. They were compiled at regular intervals by the incumbent and churchwardens, and several survive for most Leicestershire parishes. Those produced for the bishop are held at Lincolnshire Archives, with a microfilm copy at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, which also holds glebe terriers produced in other years for the Archdeacon of Leicester.

A series of glebe terriers can help to chart the progress of enclosure within a parish. The parish of Seagrave, for example, was finally enclosed by a Parliamentary Act of 1765 and award of 1766, but glebe terriers of 1730 and 1735 mention several closes. One of the glebe ‘lands’ (strips in the open fields) in Ansley Field was described as ‘above the Closs in berrygate’, and other in Nether Field was ‘next Johnsons Closs’. Johnson was presumably the landowner who created the close, or the farmer who held it when the terrier was compiled.

Enclosure by Act of Parliament

Clergy, others with only a life interest in the land, and those holding land as a trustee had no power to agree a settlement that would be binding on future generations or beneficiaries. Most parishes would have included some land in one or more of these categories. To prevent future disputes, such enclosures needed to be agreed by Act of Parliament. This became the most common form of enclosure in the county from the 1750s.

Between 1751 and 1800, 134 enclosure Acts were passed for Leicestershire parishes. In 1794, agriculturalist John Monk wrote of Leicestershire, ‘There are very few open fields in the county; and those few, in all probability, will be inclosed in the course of a very few years’. To simplify the process and reduce the costs of preparing individual Acts, in 1801 Parliament passed a Public General Act which allowed local commissioners to agree enclosures within broad parameters through delegated powers. By 1842, all the land in Leicestershire had been enclosed.

Enclosure by Parliamentary Act and Award could be a lengthy and expensive process. The landowner(s) seeking enclosure needed first to seek the support of other major landowners in the parish. If they were favourable, a public meeting would be called, where any landowner could express their support or concerns. If owners of three-quarters or more of the land in the parish agreed, they would instruct lawyers to prepare an Inclosure Bill, naming the commissioners who would be appointed to oversee the process, and then arrange to have the bill presented to Parliament. If the bill passed its readings and the committee stage, it became an Act.

Many Enclosure Acts for Leicestershire are held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, and others are held in the diocesan archives at Lincolnshire Archives (as they affected the owners of glebe land and tithes). The Acts contain information about the promoters of the scheme.

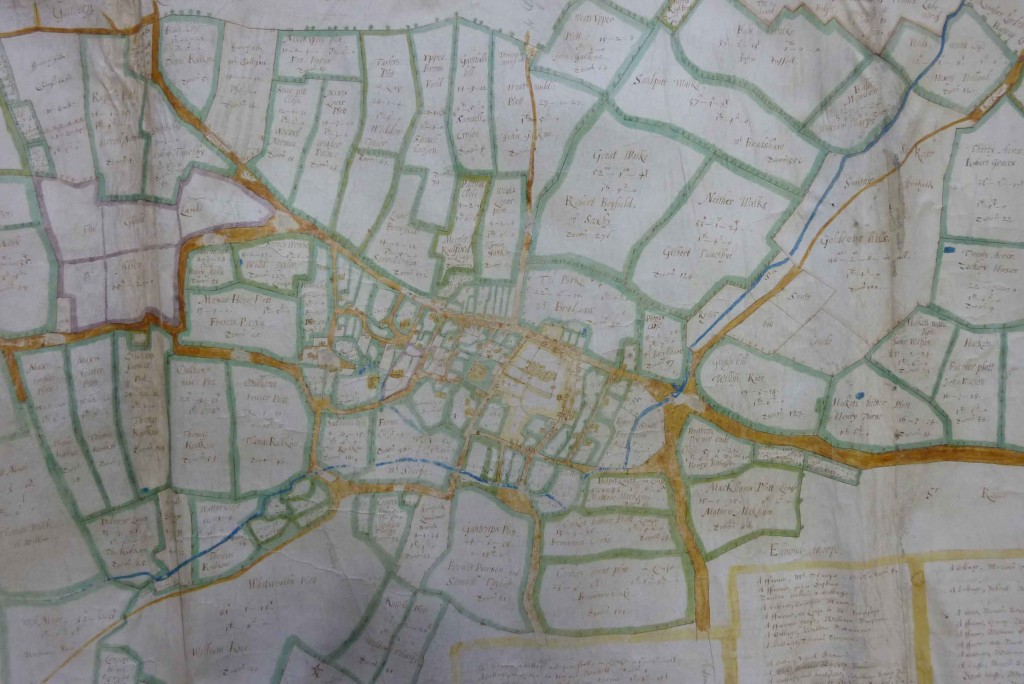

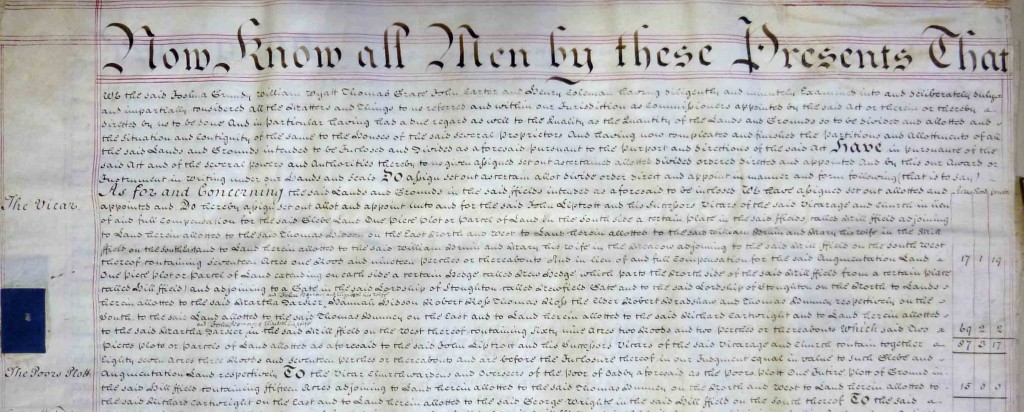

The Act was followed by the appointment of commissioners to appoint a surveyor to produce a map of the land to be enclosed, to meet with landowners to hear their claims and to devise an apportionment of land that would satisfy all those with legal rights. There would often be three commissioners, one to look after the interests of the lord of the manor, one for the tithe owner and one to protect the interests of all other landowners. The map would be overlaid with the proposed new roads and new allotments of land, and shown to landowners. Once any legal challenges were overcome, the apportionment would become a binding award.

The earliest awards tend to be written on large sheets of parchment measuring several feet across in both directions, while later awards were usually bound into a more manageable book. In both cases there are usually marginal notes signposting each of the individual allotments and the other important points. There would usually have been three copies: one enrolled with the county, one given to the incumbent to hold on behalf of the parish, and one for the lord of the manor.

Copies of the award survive more frequently than the maps. A list of surviving enclosure maps can be found in R.J.P. Kain, J. Chapman and R.R. Oliver, The Enclosure Maps of England and Wales 1595–1918: A Cartographic Analysis and Electronic Catalogue (Cambridge, 2004). For more information about these maps see our guide to Maps before the Ordnance Survey.

Surviving minute books of the meetings of enclosure commissioners can sometimes provide details of negotiations and objections. The process transformed the landscape. Large prairie-type fields were divided into small closes, straight roads created to link villages where there had only been meandering muddy footpaths, and in some places even streams were straightened or diverted. A farmer might have had 100 individual strips of land spread across the whole parish, which were exchanged for a compact block of land. There was a huge amount of work to be done, and a limited time to make the changes between the harvest and sowing the next year’s crops. Once the apportionments were made, new leases had to be agreed. Owners then had to hedge their boundaries and pay a share of the overall costs, which could amount to between £3 and £10 for each acre.

What to look for in an enclosure award

The key points to look for in an enclosure award are:

How much land was enclosed – was it the whole parish, or was part of the parish already enclosed or left unenclosed? Were earlier enclosures included, either to achieve a neater apportionment of land or to take the opportunity to completely extinguish tithes?

How many open fields were there immediately before enclosure? By the mid-eighteenth century many parishes had 4, 5, or 6 field rotations.

Were tithes extinguished and, if so, was that achieved by the allotment of land to the rector (not always a clergyman) or by the agreement of ongoing ‘corn rent’ payments? Power was divided unequally, and tithe owners were in a strong negotiating position. Landowners were often prepared to give up more than the logical one-tenth of their land for the benefit of retaining all the proceeds of any additional productivity.

How much power does the major landowner appear to have? Does he get the best land?

Were the new lands laid out in a way that was convenient to the farmers, or were some farms a long way from the farmer’s house? Does a modern map show any farmhouses built in the enclosed fields?

How many landowners were there, and how many acres did each have within the parish? The acreage of each does not necessarily match the size of the farm, as a large landowner might let his land to several farmers, or a smaller owner-occupier might rent additional land to give a larger farm. Farms can also extend across parish boundaries. However, any indication of the size of farms will add to your understanding of farming in the parish.

Were there many small awards (under 5 acres)? These may not have been economic to hedge or to farm, and may have soon been sold to neighbouring landowners.

Try to identify where any old enclosures mentioned were situated (road descriptions may help to locate them if there is no map).

Note any furlong and old enclosure names mentioned, which may give clues to earlier land use.

What public roads were planned? Were they constructed? Did anyone have a private road built at the expense of all the landowners in general?

Does the village enclose before or after its neighbours? Is it possible to work out what the trigger for this enclosure was?