Before 1833, the establishment of a school depended upon donations from a benefactor, or a sufficiently large and wealthy population to support a private school. Provision varied widely from parish to parish and purpose-build schoolrooms were rare. The curriculum depended on the whim and abilities of the schoolmaster, perhaps tempered by the actual or perceived requirements of parents. Schools could (and did) close when their financial position changed, and evidence of a school, or a schoolmaster, in a village on two separate dates should not be taken as an indication that some kind of school existed for the whole of the intervening period.

This guide will lead you through the sources you need to check to compile a history of education in your parish. Sources appear in bold red bullet points, while the text provides examples and explanations to help you to interpret your findings.

Schools before 1547

There were few schools in Leicestershire in the Middle Ages. Those that existed were not recorded systematically for any single purpose, so references to a school in the Middle Ages are only likely to be discovered during a search of medieval documents during the course of a much wider research project. Most of the records that do survive will probably have already have been spotted by someone in that way. Check to see if a school is mentioned in the chapter on education in volume III of the Victoria County History for Leicestershire, or in any history written about the parish in the medieval period. If so, and the author has provided details of the source used, you should find that document for yourself, as it may contain more information.

One of the earliest records we have for Leicestershire schools appears in the Patent Rolls of 1347. England was at war with France, and the assets of the Cluniac priories, whose mother house was in France, had been seized by the king. They included the ‘schools’ (note plural) of Melton Mowbray, which on 10 July 1347 were transferred into the custody of Robert Porter of ‘Codyngton’ for as long ‘as the war shall endure’. Brethren and priests elsewhere in the county may also have provided education to local children. That came to an abrupt end at the Reformation, with the dissolution of the monastic houses, religious gilds and chantries. Although the number of children they taught would have been small, their influence may have extended much further if some of those children provided informal tuition to others in later years. Surviving wills and probate inventories from the first half of the sixteenth century show that even in small villages there was often more than one person who could write.

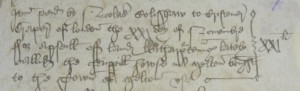

Only one place in Leicestershire is mentioned as having a school within the records created in 1547 on the dissolution of the chantries: in Castle Donington, a chantry priest at had taught ‘a grammer schole … for the erudycyon of pore scholers’. If there were other similar schools elsewhere in the county, their existence was hidden from the Crown commissioners. Some parishes managed to obtain royal agreement to retain gild or chantry funds to provide a school as an act of charity for poor children, but such agreements were exceptional. One such was in Melton Mowbray, where the churchwardens accounts for 1549 (depicted below) include £21 ‘paid by Nicholas Colisshaw to Cristoner Draper of london the xxi dey of Novembre For a p[ar]sell off land withapp[er]tenn[en]ces lately callid the cheippill howse in Melton bought to the Town of Melton use’.

This chapel-house, which had probably belonged to a religious gild now abolished by law, had come into the hands of Draper, but the town had decided to buy it from him for the benefit of its people. The accounts show that the money required had been raised through the sale, also in London, of a silver-gilt and gold pyx and other valuable church plate that was not required for the newly-introduced Protestant form of worship. They may have suspected that such valuable items would be next on the list for confiscation by the Crown, and took their opportunity to gain some benefit for the parish before that could take place. Later entries in the churchwardens’ accounts suggest that this building was then used by the town as a school, as it may also have been before the Reformation.

Schools between 1547 and 1833

A number of different types of school developed in the centuries following the Reformation, from those which offered training in the Classical languages and prepared pupils for university to those which may have offered little more than a child-minding service. In many cases we know little about the curriculum they offered, but it is often possible to discover how they were financed, and as that could affect the number and social status of the children who attended and the ethos of the school, it can be a useful form of classification.

Regulations were introduced in 1563 requiring all schoolmasters to subscribe to the 39 Articles of Religion agreed by the Anglican Church that year. This precluded Roman Catholics and many Protestant dissenters from teaching. From 1604, schoolmasters had to hold a diocesan licence, ensuring conformity. This created two kinds of record, from which we can infer the existence and location of schools:

- Subscription books will identify schoolmasters in your parish. These are held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland and there is a handwritten index to them.

- Visitation and church court records may identify those teaching without a licence. Like other Leicestershire records created by the Anglican Church, some of these documents are held at Lincolnshire Archives, while others are held by the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland.

Licences continued to be issued until the early 19th century, even though the prohibition on Protestant dissenters becoming teachers was lifted in 1770. Those records relating to the period 1600-1640 have been listed in B. Simon (ed.) Education in Leicestershire, 1540-1940 (Leicester, 1968), Appendix I.

The schools themselves fall into three broad categories: endowed schools supported by permanent capital, voluntary schools dependent on subscriptions, and private schools charging parents for the full cost of the education delivered. Sunday schools began to appear from the 1780s, and can be considered as a specific type of voluntary school. By the 1830s many of these had begun to also provide classes on weekdays, and for a few decades the distinction between Sunday and weekday schools can become blurred.

Endowed schools

Endowed schools, sometimes known as charity schools, free schools or (before 1870) as grammar schools had a permanent capital base and usually a building. They include some of the oldest schools, and are usually the easiest type of school to research. Their endowment – a donation held by trustees and invested to provide an income to pay the running costs of the school, including a salary for the schoolmaster – gave them a secure existence. Most survived with very few changes from the date of their foundation until the reforms of the 1870s.

A foundation deed sets out how the school was to be organized and run: how the master was to be chosen, the number of children to be taught, any restrictions on who could receive a free education, and sometimes also the curriculum. Those schools that were required to teach Latin and possibly Greek were known as grammar (or Classical) schools. As such schools arose from individual acts of charity, some large schools might be in very small villages. Sir John Moore’s school, midway between the small villages of Appleby Magna and Appleby Parva, was founded in 1699. The endowment provided a total of £175 annually for a headmaster, English master and writing master, who taught 50 boys ‘Greek, Latin, English, writing, &c.’. Most endowments were far smaller, for example the endowment for the school at Broughton Astley provided just £4 10s. per annum, which enabled 8 poor children to be taught. Many places, including some quite large settlements, had no endowed school at all.

The fullest details of the terms governing these early endowed and grammar schools can be found within a report of the Charity Commissioners’ to parliament in 1839. Details of the charity’s annual income and the number of scholars is usually included within a return made by all parishes to parliament in 1819:

- Reports of the Commissioners of Charities, Parl. Papers 1839 (163)

- Education of the Poor Digest, Parl. Papers 1819 (224)

These two sources can often provide other useful information. The 1819 return tells us, for example, that two acres of land belonging to the school in Thornton had been ‘lost’ through mismanagement, while at Market Bosworth an endowment producing income of £700 per annum had been ‘thrown into Chancery’ so no children were being taught. Local record offices tend to hold only a small number of parliamentary papers, but they are all held by many university libraries.

Details of endowed schools should also appear on

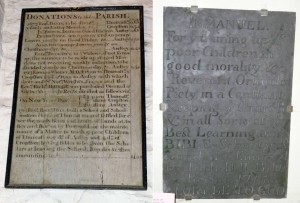

- Charity boards in parish churches

In an attempt to ensure that charity funds were not diverted elsewhere or lost through fraud or maladministration, from the late 18th century archdeacons insisted on the details of all parish charities being painted on boards that were to be hung in the church, and many of these boards remain there today. A board still hanging in Thurcaston church, for example (shown below), records that in 1715 the ‘Rev’d Rich’d Hill built a School and Schoolmaster’s house at Thurcaston and settled for ever the yearly Rents and Profit of lands at Anstey and Burton by Prestwold for the maintenance of a Master to teach 9 poor children of Thurcaston, 9 ditto of Anstey and 4 ditto of Cropston: buying Bibles to be given the Scholars at leaving the School.’ These can reveal details of charities that existed in the late 18th century when the donation was recorded, but which had been ‘lost’ when parliament called for returns in the 19th century.

- Engraved plaques on school buildings

Some donors ensured their benevolence would be known and remembered by all through the provision of an engraved plaque for the building. Richard Hill’s plaque, engraved on local slate, used to be on the schoolroom he provided, but is now in Thurcaston church. A few miles away in Mountsorrel, Joseph Danvers provided a school in 1742 for 8 poor boys from Mountsorrel and 4 from Swithland, and the building still displays the donor’s name on an outside wall.

Voluntary or Subscription schools

The foundation of the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) in 1699 encouraged clergy to seek subscriptions to help to establish a school in their parish. It was supported locally by two bishops of Lincoln, Dr William Wake (1705-16) and his successor Dr Edmund Gibson (1716-23). They required every incumbent to complete a questionnaire as part of the triennial episcopal visitation, which asked a specific question about schooling in each parish.

- Bishop Wake’s four visitations of 1706-15. The details provided by incumbents to the bishop’s questionnaires are held at Christ Church, Oxford, but have now been published: J. Broad (ed.),Bishop Wake’s Summary of Visitation Returns from the Diocese of Lincoln 1705-15: volume II, outside Lincolnshire (Oxford, 2012).

- Bishop Gibson’s visitations of 1718 and 1721. The original handwritten responses of the clergy are held at St Paul’s Cathedral library, but there are microfilm copies of these at Lincolnshire Archives.

The following two examples show the type of information you will find here. Bishop Wake was told in 1706 and 1709 that there was no school in Blaby, but in 1712, rector Edward Lovell reported that he was collecting subscriptions for a charity school ‘to teach our miserable poor to spin, read write & to learn and understand the Church Catechism’. By 1715, donations amounted to £4 a year, and six children at a time were being taught how to spin. The replies to Bishop Gibson’s articles of 1718 reveal that there were six donors in all, including the rector. In contrast, there was no school in Wigston, and vicar Edward Jolley reported to Wake in 1712 that ‘There never was and Ime [sic] afraid never will be any thing of this nature at least in this generation so far as I can yet forsee’. Nothing had changed in Gibson’s time, with the vicar believing the lack of a school to be one of the reasons why nonconformity was flourishing, ‘but the worst of all’, he added, ‘we know not how to remedy it’.

Subscriptions provided an uncertain future, and it cannot be assumed that any schools identified in these returns had a continuous existence. Without an endowment, they are also unlikely to have had a schoolroom before the 1830s. Some teachers might have taught a few children from their home, while others (perhaps clergy) taught in the only community building in their village: the parish church. After the Reformation most parish churches held no more than four communion services each year. The side chapels and even the chancel of a medieval church were rarely used for parish worship, and desks and chairs could be set out without the need to pack them away each weekend. There would have been a Bible, to teach reading, and the children could conveniently be taken to join midweek services.

By the 1780s, Sunday schools were being established in many parishes. Literate parishioners might offer their services gratuitously to teach reading on Sundays, and other costs were often covered by collections taken at annual sermons, advertised in local newspapers. Anglican church visitations from the late 18th century also include details of schools and teaching, and you should check:

- The visitations held by archdeacons Bickham (1773-9), Burnaby (1793-7).

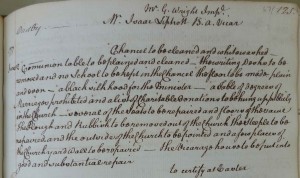

These visitation records are visitation books rather than questionnaires, and are held at the Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland. These reveal that many parish churches were being used as schools for part of the week. The use of the chancel in this fashion led to the admonishment of the rector of Oadby in 1777. The archdeacon’s complaint in this case is only that children were being taught in the chancel, the most sacred part of the building, although his instruction when he visited Eaton in the same year was that ‘no school [was] to be kept any longer in the church’. At Long Clawson, ink had been spilled on the communion table, and this may also have occurred at Eaton, where the incumbent was asked to see that the communion table was ‘repaired and cleaned and painted’. (The Record Office for Leicestershire, Leicester and Rutland, 1D 41/18/21 fols. 67, 133v, 139v). It is not always clear whether the schools mentioned in these reports were day schools or Sunday schools.

Physical evidence of the use of churches as schoolrooms survives in a few parishes, including in writing on the inside of the door in the north chapel at Lubenham (which is difficult to date) and an additional external entrance created at Husbands Bosworth (below).

The north transept of Medbourne church also functioned as a school room, and ‘J.T.’ recounted to Leicestershire’s historian John Nichols how when he was a pupil there (in perhaps the 1740s-50s) the master and scholars used to pass through a door from the school room into the body of the church for prayers every Wednesday, every Friday, every saint’s day, every day in Passion week and in the week before Whit Sunday.

Subscriptions are also mentioned in

- Education of the Poor Digest, Parl. Papers 1819 (224)

For example, the return from Thrussington advises that ‘The parishioners have erected a small school-house and room … supported by an annual subscription’. That said, it is not always possible to distinguish between subscription and private schools within that return, as there was no requirement to specify how a school was funded.

The monitorial system

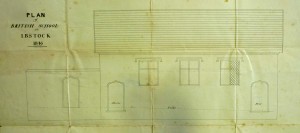

A non-denominational society, the Royal Lancasterian Institution for the Education of the Poor, was founded in 1808, to provide schools and teaching to poor children, mainly in towns and the largest villages. It took its name after educationalist Joseph Lancaster, but distanced itself from him in 1814, and changed its name to the British & Foreign Schools Society.

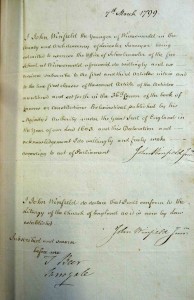

In 1811, in response to the growth of non-denominational Lancastrian schools, which were viewed by some as a threat to the Anglican Church, the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church was formed. National schools (as they became known) were Anglican, and those managing them had to sign an undertaking to teach the Church of England liturgy and catechism, and to ensure that the children educated there attended service in the parish church each Sunday. The National Society provided grants to its own schools, and affiliated schools in Leicester Archdeaconry were able to apply for financial help from 1812. This may account for the society’s early growth in this county. In contrast, the British & Foreign Schools Society had little money in its early years, and the number of its schools in Leicestershire was never very large.

- A set of the annual reports of the National Society is held at Lambeth Palace Library, and an incomplete set by the British Library. The content varies from year to year, but there are intermittent lists of schools, sometimes with details of grants, numbers of pupils and occasionally other information.

- National School files are held at Lambeth Palace Library for most schools connected to the Anglican church, including some not formally designated National Schools, and can contain a wealth of information that is not available elsewhere. As the bulk of their contents relate to the period after 1833, these will be described in more detail in the guide covering the period from 1833 to 1902.

- The British and Foreign Schools Society archive includes the society’s annual reports, correspondence with individual schools and details of grants awarded, and is held at Brunel University.

Teachers faced the practical difficulty of teaching a large group of pupils of all ages, who might attend irregularly, and who would require teaching at different levels. The National Society and the British and Foreign Schools Society adopted their own (slightly different) methods of teaching to overcome this issue.

Anglican clergyman Andrew Bell devised his method of teaching in the early 1790s, when superintendent of the Male Orphan Asylum at Madras (now Chennai), India. He copied a system he had seen locally, in which the more able children taught those who had not yet learned as much, and were themselves taught by more advanced scholars or by the teacher. On his return to England in 1796, Bell published a pamphlet on this method, which became known as the Madras system, or Dr Bell’s system. It was used widely in National schools, and was sometimes also called the ‘National system’.

A similar monitorial system was also devised independently by Quaker Joseph Lancaster in a school he established in 1801 in Southwark, London. He published details in 1803, and his book attracted the attention of bishops, parliamentarians and the king. Lancaster’s system was adopted by schools affiliated to the Royal Lancasterian Institution, later known as the British & Foreign Schools Society.

By using one of these monitorial methods of teaching, even the largest school needed just a single room and one master, which kept costs down. The children would sit at rows of desks facing the master, who decided what would be taught each day. A Lancastrian classroom originally built for 300 boys and 30 monitors, survives at the former British School at Hitchin (now the British Schools Museum). Inscribed semi-circles on the floor along the two main walls mark the teaching stations, where monitors would instruct small groups of boys using teaching sheets designed by Lancaster, which were hung from the walls. Curtains would hang between these stations to prevent the children being distracted by the teaching at the next station. The work was graded, with children learning together according to the standard they had reached, but as attendance was not compulsory each group would be of mixed ages. Between the taught sessions they would practise their lessons at their desks using slates, except the children in the lowest standard, who wrote their letters in trays of sand. The classroom floor in British schools sloped up to the back, in the manner of a lecture theatre, so the master could see all the pupils from his desk at the front.

Private schools

By 1818, almost three-quarters of all of Leicestershire’s towns and villages had a day school, and most of these were private ventures (sometimes known as ‘adventure schools’, which sounds far more exciting than the reality). Private schools were simply schools which took fee-paying pupils and operated for profit. They ranged from schools providing an advanced education that only the gentry and higher middle classes could have afforded, to ‘dame schools’, which sometimes offered little teaching beyond the alphabet for a small sum each week. Like subscription schools, private schools could be short-lived, as they required a steady stream of pupils whose parents could afford to pay.

The division between private schools and others is based on how they were funded, but many may have had similar pupils. Some private schools taught a few children whose education was paid for by a charity, alongside the fee-paying children of the better-off. Conversely, the masters of some endowed schools were permitted to take a number of paying pupils to supplement their salary.

At the schools offering a wider curriculum, fees could be substantial. The Leicester Chronicle for 7 January 1832 includes advertisements for several private schools. They include a school at Fleckney which advertised lessons in ‘the English and Latin Grammars, Reading and Recitations, Plain and Ornamental Penmanship, Arithmetic, Book-keeping, Land Surveying, &c.’ and charged five guineas per quarter for boarders, three guineas for day boarders and fifteen shillings for day pupils. The Classical and Commercial Academy at Billesdon, another boarding school, charged 21 guineas annually. Run by a dissenting minister it advertised tuition in French, classical literature, ‘those parts of learning most necessary in trade and in commercial pursuits’, and boasted its pupils ‘have produced specimens of Penmanship and of Mapping that have excited admiration’.

An overview of school provision

Towards the end of this period, and as intimated above, an overview of school provision for the children of the poor is provided in a set of returns requested by parliament from parish clergy in 1818.

- Education of the Poor Digest, Parl. Papers 1819 (224)

This gives details of the day schools and Sunday schools that provided free or low-cost education to children from the ‘working-classes’, including those schools that educated a few poorer pupils alongside the children of those who could afford full fees. The following two consecutive entries, for a large and a small village, give a flavour of the type of information this return contains:

| Parish and name of minister signing return | Population [in 1811] | Particulars relating to endowments for education of youth | Other institutions for the purpose of education | Observations |

| HathernS.T.M. Phillips, rector | 1,098 | A free school for boys, open to all who rent less than £10 a year; the numbers there vary from 10 to 50, at present there are only 10. The master is paid £10 per annum by a principal family in the village, upon whose ground the school-house was built by voluntary subscriptions, and £5 more is added by trustees of lands left to the poor of the parish, for instructing 10 scholars in writing. The master has a house, rent free, and a considerable number more children would attend, if the duties were efficiently performed. | Two Sundays schools for girls and boys, comprising about 250 | The poor have sufficient means of education; and the minister observes that there are lands left to the poor of the parish, the rents of which amount to about £50 but the designation is not known, as the original deeds are lost. They are vested in trustees, and the profit annually expended in linen, which is distributed to such parishioners as do not receive parochial relief. |

| HeatherP. Belcher, rector | 334 | None | A Sunday school, containing from 30 to 40 children, supported by the rector; and a day school, consisting of the same number. | The poorer classes are very desirous of having their children instructed. |

As with any historical source, you need to consider any possible bias. It is interesting that in Hathern, where only 10 boys attended a day school from a total population of over a thousand, the rector thought there were sufficient educational opportunities in the village. He probably thought that what was taught at Sunday school was enough of an education for the poorer classes, even though it may have been little more than the church catechism, Bible stories and some reading. There appears also to be some disagreement between the rector and the schoolmaster, with the rector believing the master was neglecting his duties. In Heather, the rector believed the poor wanted access to education, and may have been trying to encourage donations from parishioners to subsidise this. There are no clues in this source to the type of education he thought appropriate, and his interest may have been to draw pupils and their parents closer to the Anglican Church.